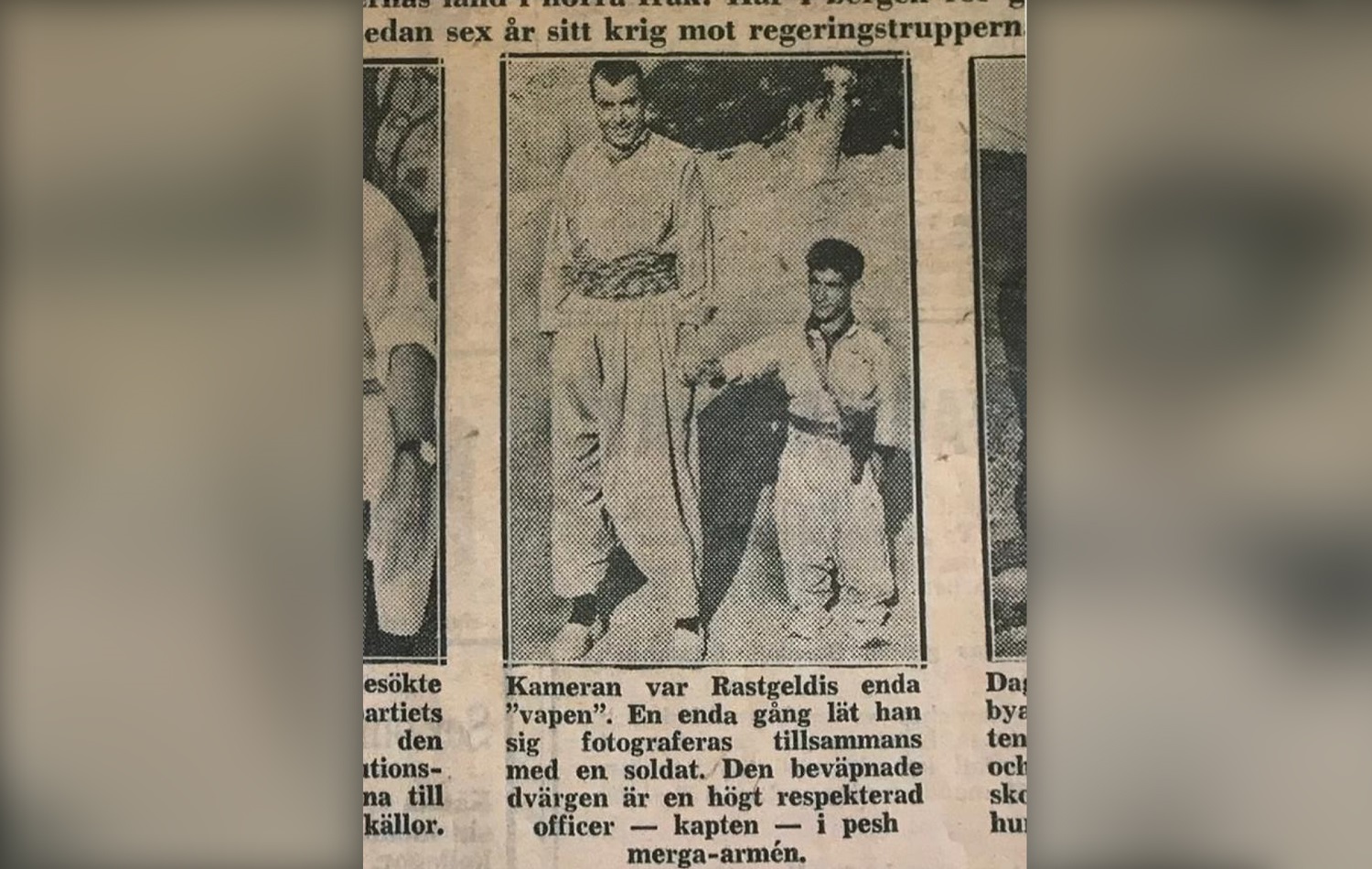

Dr. Selahaddin Rastgeldi in the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan, where he documented the events of the September Rebellion, in 1966. Photo from the archives of Rastgeldi's relatives

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — The men were paraded naked, then mounted onto poles pushed into their anuses. Inanition and deliberate sleep deprivation made them hallucinate. Beyond dungeon walls, British men in shorts and women in bikinis played on the Yemeni shoreline with their children, unaffected by the depravity being enforced by their compatriots. To add insult to injury, the interrogators forced the detainees to urinate and defecate in their cells.

Determined to investigate the conditions of British-run detention, a 39-year-old Kurdish physician landed in Aden on July 28, 1966.

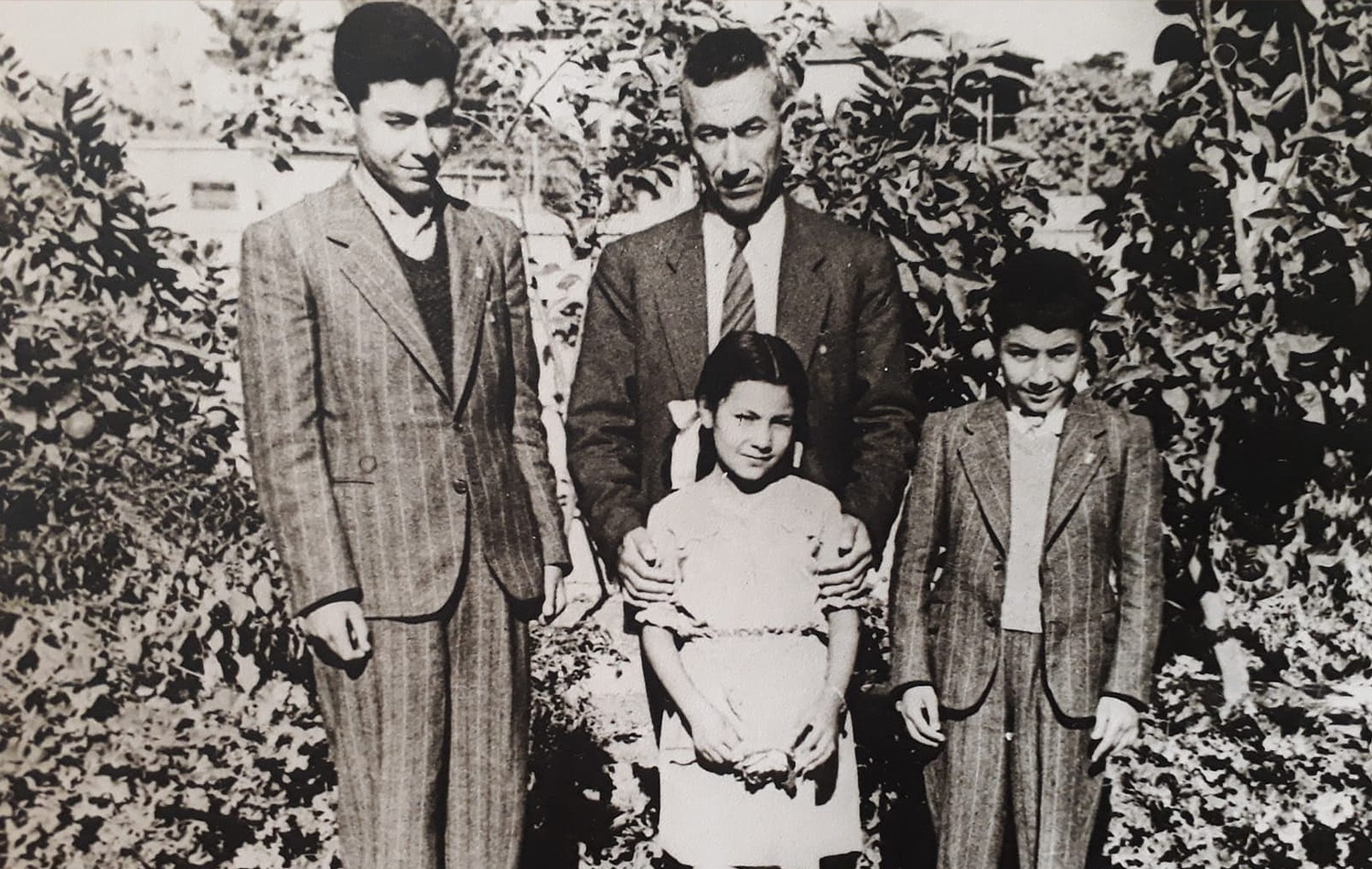

Selahaddin Rastgeldi grew up in a country no stranger to rights violations. He was born in 1927 to a well-to-do family in Turkey’s southeastern province of Urfa and educated at a prestigious American college in Istanbul, before he moved to Sweden in 1947 to study, then practice medicine. He worked at several Swedish hospitals before opening his own surgery in the affluent Stockholm neighbourhood of Ostermalm.

As one of the first ever Kurds known to have settled in Sweden, Selahaddin was determined to raise as loud an alarm as possible about the human rights violations happening in the four countries most Kurds reside in. His passion for human rights, particularly for fellow Kurds, brought him into contact with some influential Swedes who cared deeply about the Kurdish issue.

By the early 1960s, Selahaddin had become a member of the executive committee of the Swedish section of Amnesty International, then a new human rights watchdog established by British lawyer Peter Benenson. With the birth and rise of organisations like Amnesty, a window was finally being opened onto the horrors of torture in political detention. It was in his capacity as an observer for Amnesty that the Kurdish doctor arrived in Aden to investigate reports that the British were applying inhumane interrogation techniques to Yemeni political detainees, some as young as 16 years old.

Selahaddin’s fight for the under-trodden is a testament to the complex nature of identity politics in his country of birth. Kurds in today’s Turkey are still deprived of an effective political voice, and Ankara’s authorities continue to use every tool at their disposal to silence pro-Kurdish movement, including the imprisonment of political activists. Of the 65 mayors elected on the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party ticket in the municipal elections of 2019, 59 have been forced out or detained.

Despite the pressure on Kurds in his homeland to assimilate into wider Turkish society, Selahaddin would use every opportunity in his life in Europe to proclaim his Kurdishness – to the discomfort of many in his own family.

In the mid-twentieth century, Aden was second only to New York as the busiest harbour in the world. The strategic port served British trade routes to India and East Asia, and was valued as a developing British commercial interest in the Middle East. The city's sprawling military base effectively served as the headquarters of the British Middle East Command, at a time when the tentacles of Empire were being forced to recoil. With the decolonisation movement in global swing, the Yemeni people too were demanding that the British leave. By the end of the 1950s, the Yemenis had launched an insurgency to expel the colonisers. The British had faced similar rebellions in other colonies, so applying the brute force it needed to silence opponents and avoid public scrutiny now came as second nature.

Colonial repression was stepped up after a grenade was hurled at Aden airport, where British High Commissioner Sir Kennedy Trevaskis was waiting to board a plane, on 10 December 1963. The British ordered the imposition of State of Emergency laws, and civilians were rounded up on the pretext of having collaborated with the nationalist insurgents. With little to substantiate their allegations or turn the tide of the Yemeni insurgency, the British began to torture detainees to obtain intelligence.

Soon enough, reports of torture began seeping out of British detention centres to Arab human rights groups. By 1965, these reports inundated the offices of both Amnesty International and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

"I was detained in a British interrogation centre... for eight months," protest organiser Abdul Razzak Shaif recalled some twenty years after his detention. "I received electric shocks and other vicious things were done to me. Many of us who were tortured were permanently damaged, I was not an exception."

By the time Selahaddin arrived in Aden, new High Commissioner Sir Richard Turnbull had been in power for a year. The career colonialist had moved to Yemen from Kenya, where as Minister of Internal Security and Defence he orchestrated an infamously brutal crackdown on the Mau Mau rebels. Selahaddin faced off with Turnbull, adamant that he would interview the Yemenis held in British detention. The High Commissioner was equally intransigent, dead set on denying the Swedish-Kurdish physician the access he needed to uncover torture.

While Selahaddin sought proof of the abuses taking place behind prison doors, the brutality of the British soldiers was in plain sight on the streets of Aden, where innocent people were being gunned down.

"We were so tuned in and so keyed up to get results, that I think we took everybody to be a potential terrorist... they were gollies or blackies or whatever, and yes we had an internal security program which we worked to, and that would actually have golly hunt on it," Brian Roy, one of the soldiers on patrol in Aden in 1967 recalled in a documentary years later. "We had people who, in some cases, lost control, lost discipline and just let loose in sheer fear of their lives, they were those who sought to gain glory by shooting innocent people, that did happen, it was one of those things, it did happen."

Selahaddin met the High Commissioner two days after his arrival in Aden, the names of 164 political detainees in hand. Turnbull rejected Amnesty’s categorisation of the detainees as political prisoners, instead labelling them as either "terrorists or associated with terrorism as couriers, suppliers of weapons, etc,” or as being “educated and prepared as terrorists". But Selahaddin refused to cave in. "I asked if I could visit a prison where simple criminals and terrorists were kept. The High Commissioner would not allow me to visit any prisons. Amnesty was completely given the cold shoulder," he wrote in his report for Amnesty International, dated December 1, 1966 and made available online by the organisation half a century later.

Unfazed by the immovable Turnbull, Selahaddin instead spoke to a number of former detainees and the families of those still in detention to prepare a damning report for Amnesty. The Swedish section of the organisation released the report, and Selahaddin went on the BBC to provide a scathing account of what the British were doing in Aden. But Amnesty's main office in London dragged its feet, and delayed the report’s publication.

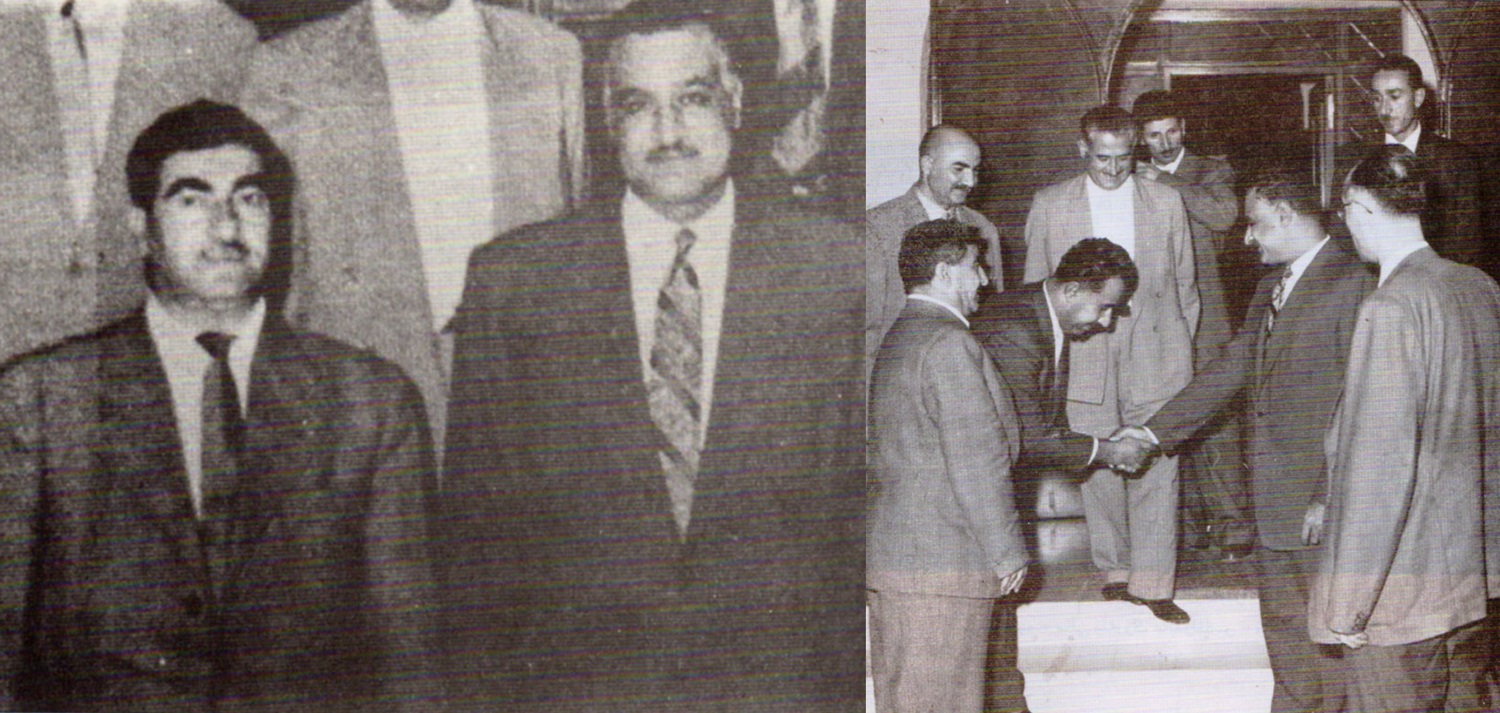

Anonymous British officials spread rumours in the sympathetic national press that the head of Amnesty in Sweden was a Communist sympathiser. Selahaddin was described by British government officials as being in the pocket of the Egyptian leader Jamal Abdul Nasser, who was a thorn in colonial Britain’s side and a sympathiser with the Kurdish liberation movement. They based their assertions on Selahaddin on Nasser’s close ties to the Yemeni rebels, and the 1958 Cairo visit of charismatic Kurdish leader Mala Mustafa Barzani, who had just returned to Iraq following 11 years of exile in the Soviet Union.

But Amnesty's London headquarters had its own links that it had tried to keep under wraps – links with the very government the Kurdish doctor’s report placed under glaring light.

"A year after the Aden investigation it would emerge, to Amnesty's enormous embarrassment, that the organisation was secretly being funded by the British," wrote investigative reporter Ian Cobain in his book Cruel Britannia: A Secret History of Torture, published in 2012. "A mysterious and generous backer identified in internal correspondence only as 'Harry' was, in fact, Harold Wilson's government."

In 1967, the British government admitted that torture had been committed in its detention centres in Aden. That same year, the British abandoned its colony altogether.

Amnesty's founder Benenson displayed poor leadership in the whole affair, and his proximity to the establishment cost Amnesty dearly in terms of its reputation. Turning on the former benefactors of the organisation he had founded, Benenson lodged a case at the European Court of Human Rights against the British government in November 1966 for damaging Selahaddin's reputation. But the case never came to be, having been “struck out of the list” on October 2, 1967 “because the applicants withdrew their application before the Commission," the court told Rudaw English in August. Rudaw English contacted Amnesty International to ask why the application had been withdrawn, but received no response.

Selahaddin’s perseverance in uncovering detainee torture in Yemen was a testament to a lifelong will to speak up on human rights abuses, an unsurprising quality considering his background. After all, he was a proud Kurd from Turkey, where successive ultra-nationalist governments had launched a full assimilation policy primarily targeting its sizable and restive Kurdish population. State-inflicted violence was part and parcel of everyday life in Turkey, and the Kurds were at its receiving end more than any other group.

The voice of Kurdish rebels

In May 1965, Jamal Alamdar was a 25-year-old civil engineering student living at a refugee facility in Soderkoping, some 180 kilometers south of the Swedish capital. One day that month, Almadar was told that a man was waiting for him at the facility’s reception; Selahaddin had turned up in a white Porsche to pick him up and take him to Stockholm.

Jamal was a native of Erbil and a member of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), one of Iraq’s main opposition parties to heavy-handed central government rule. He lived in Turkey for seven years, from 1958 onwards. In 1960, popular Turkish prime minister Adnan Menderes was publicly hanged from the gallows after a coup d’état, and the country was brought under the yoke of the generals. Defying the steely grip of the military, Jamal established a Kurdish students’ society, with the help of some other Kurdish students from Turkey. He was soon whisked away from his Istanbul home by the Turkish secret service, forced to endure sleep deprivation, foot whippings, and whole body beatings with a wooden club. He told Rudaw English in August that he would have been freed had he signed a statement implicating other members of the group, but he flatly refused the deal.

Upon his release, Jamal sought resettlement in Sweden. He approached the Swedish consulate in Istanbul, where the head of mission would surprise the young engineer. "He knew about the Kurds, and said there was a very active Kurd in Sweden called Selahaddin Rastgeldi," Jamal told Rudaw English. "He advised me to go and see him when I arrived in Sweden." To Jamal's astonishment, the Consul General had contacted Selahaddin and told him about the newcomer’s place of residence. Selahaddin invited Jamal to his flat in Stockholm, where he stayed as a guest for two weeks.

Selahaddin grew increasingly nationalist during his time in Sweden, associating with Kurds from all parts of Kurdistan. Rohat Alakom, a Kurdish author who researched Selahaddin’s life, said that the doctor’s dive into Kurdish nationalism was aided by his links with Kurdish student activists across Europe, as well as the prominent Kurds from Syria and Turkey that he would come to meet.

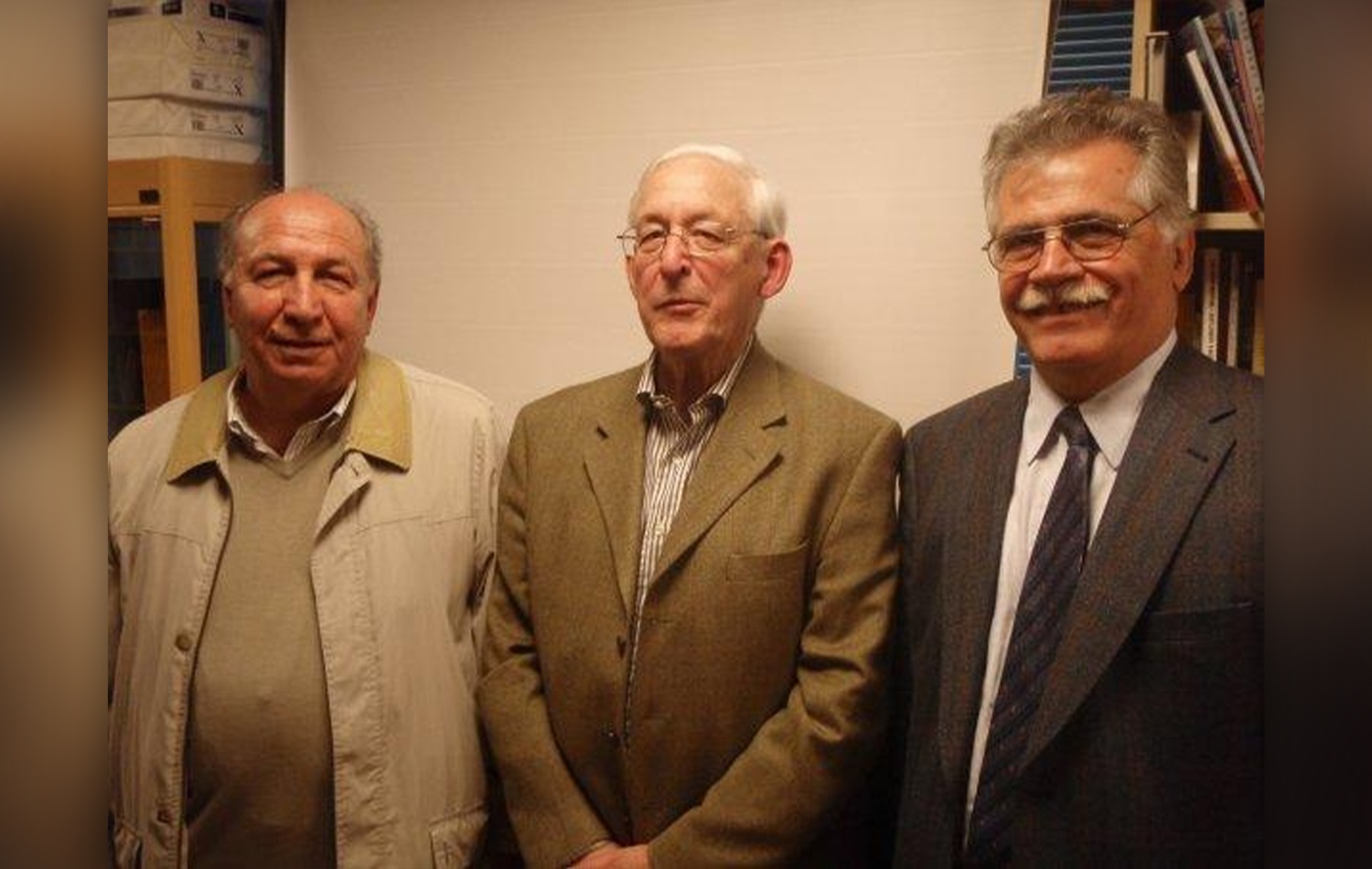

Selahaddin and Jamal teamed up with a group of influential Swedes sympathetic to the Kurdish cause to establish the Swedish-Kurdish Committee in early 1966, shedding light on atrocities committed against the Kurds in Iraq and promoting Kurdish rights across Europe. According to Omar Sheikhmous, a towering, Sweden-based figure in the Kurdish nationalist movement who knew Selahaddin closely, some of Swedish society’s most prominent were active on the Kurdish issue. Among the prominent Swedes Selahaddin mobilised were Dr. Olof G. Tandberg – International Secretary of the Swedish Academy of Sciences, and Madame Marta Hansson, chairwoman of the Swedish-Kurdish Committee founded in 1966.

Marta Hansson ran a publishing house with her husband, and agreed to foot the bills for the committee's expenses. Her care for the Kurdish issue ran deeply, and Jamal wanted to know why. “My first love was a Kurd," she told him. Marta had lived with her father, a diplomat in Cairo, in the early 1900s. One day, he gave a reception to the diplomatic community, where a guest, an Ottoman embassy secretary, caught Marta’s eye. She fell in love with Mohammad Rahim Bag, the young Kurdish diplomat, and a relationship ensued. It is not clear exactly what brought an end to their romance, but Rahim Bag left a deep impression on the young Swede, who would then become greatly involved in the struggle for Kurdish rights. The Swedish-Kurdish committee she chaired decided it would investigate the crimes being committed by Baghdad against the Iraqi Kurdish liberation movement of the 1960s.

Headed by the astute Peshmerga commander Mala Mustafa Barzani, the Kurds launched their September Rebellion against the central government in 1961, in the face of Kurdish rights violations. Almost the entire Kurdish region of Iraq had taken up the fight, and Baghdad used artillery, jets and massive manpower to quell it. When Amnesty’s Sweden branch told Selahaddin that he was going to Yemen to investigate human rights abuses, the committee agreed that once he completed that mission, he should head to Iraqi Kurdistan and investigate the rebellion in the mountains.

On the first step of his fact finding journey to the Middle East, Selahaddin arrived in London in late July. Omar Sheikhmous, who by then had begun studies at the University of London, received him. "He supported the Kurdish cause in all parts of Kurdistan, and did not treat them differently," Omar told Rudaw English in August.

Selahaddin was a prolific writer during his medical career, but his work did not come without trial and comically destructive error, Omar recounted. "One of the funniest episodes that he used to relate was that when he was doing research at the [Karolinska] medical university in Stockholm, one of his projects was to build a centrifuge to try to separate white and red blood cells," Omar said. "During one of his experiments, he had set the centrifuge to such a high speed that it exploded, and almost the entire laboratory was in danger of being destroyed."

Practising at his Ostermalm clinic, Selahaddin came into contact with many Swedes from the social elite. He became close enough to future Swedish prime minister Olof Palme to play chess with him on a regular basis, Omar Sheikhmous said.

Intent on shedding light on the ethnic cleansing that Iraq was carrying out against Kurds, Selahaddin arrived in Iraqi Kurdistan via Iran on August 18, 1966, immediately after his trip to Aden.

The Kurds were being terrorised and subjected to violence in all four parts of Kurdistan. In Iran, two decades of harsh crackdown by state security forces in the aftermath of the short lived Republic of Kurdistan in Mahabad had stifled dissent. In Syria, tens of thousands of Kurds had been stripped of their nationality and their land. And in Turkey, the suffocating assimilation policies of successive governments since the 1923 proclamation of the Republic left the Kurdish public worn. Kurds from all these parts flocked to the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan to flank commander Barzani and resist.

On one day of the mission, Selahaddin met with Barzani, to relay the committee’s efforts to shed light on the Kurdish question across Kurdistan. The commander "patiently waited until I finished taking the photos I needed, after which we went to the tent designated for guests," Selahaddin wrote in a book about his trip published in 1967 and later translated into Kurdish by Kawa Amin. "Barzani handed his old gun to one of the peshmerga, took his shoes off, and sat leaning against the tent's colours, seating me at his right-hand side."

Dr Mahmoud Osman, an advisor to Barzani and a doctor treating the peshmerga, was impressed by Selahaddin when he met him in the village of Nawperdan, near the Iranian border. "He was very well educated and... extremely devoted to the Kurdish cause, in particular in Turkey," Dr. Osman told Rudaw English on August 12.

Selahaddin asked Barzani to allow him to carry out an independent investigation on the crackdown. Barzani asked his elder son Edris to compose and send a letter to all peshmerga units, ordering that they offer Selahaddin full cooperation. The commander asked for all documents and evidence about Iraqi mistreatment of Kurdish civilians since the rebellion’s eruption to be given to the Swedish doctor.

Before Selahaddin's fact-finding mission came to an end, he went to see Barzani and asked him if he had any messages for the ICRC in Geneva, where he would be stopping off on his way home. "You have seen the situation with your own eyes, you have seen the condition of the Kurdish civilians," the rebel commander told him, according to the Kurdish translation of Selahaddin’s book about the visit.

The ICRC asked Selahaddin to prepare a report about the situation in Iraqi Kurdistan, which he delivered. His Swedish-language book about what he had seen brought the Kurdish revolt into public view, and hundreds of articles about it were written in the Swedish press.

The Swedish-Kurdish Committee ended work in 1970, when the September Rebellion had drawn to an end with a degree of Kurdish self-determination recognised by Baghdad. Selahaddin would continue to speak on Kurdish rights from Sweden for the rest of his life.

Contested Kurdishness

Selahaddin’s character and his devotion to promoting the rights of Kurds and others is lauded by his surviving family in Turkey. “He really cared about people. He was not only an idealist, a humanitarian, a civil rights advocate in political terms: he was humorous, kind, affectionate and extremely considerate,” Selahaddin’s niece Gamze Ozcurumez Bilgili, Professor of Psychiatry at Baskent University in Ankara told Rudaw English by email in August.

But Selahaddin’s stubborn claim to Kurdish identity is a sticking point among his relatives.

Selahaddin was born in Urfa, before he was moved at the age of five to the Mediterranean trade hub of Mersin by his father, a former teacher who went into merchandising. “It was very important for my grandfather that his children receive good education,” Gamze said. However, the Rastgeldi family traces its origins to Tulmen, a little village 25 kilometres to the northwest of Urfa. A young Selahaddin would make frequent visits to Tulmen until he moved to Sweden to study medicine.

It appears that at some time between his studies at Istanbul’s Robert College in the 1940s and the Turkish Republic’s first ever military coup in 1960, Selahaddin would change his outlook and proclaim his Kurdishness to the world.

While Selahaddin studied at Robert College, his younger sister Gulay was born in Mersin. Gulay, now 75, smiles as she declares her admiration for her deceased brother. But to this day, she believes Selahaddin is not a Kurd, but a Turkmen, and that his claim of Kurdish identity was about a defiance of Turkey’s status quo.

“He actually told me about his Kurdishness. I didn’t say he was not Kurdish. I didn’t make any comment,” Gulay recalled in an interview on August 22 from Ankara, where she was visiting her daughter Gamze.

Gulay explains that her family lived in proximity to Kurds – “Most of the family know Kurdish very well, our neighbours are Kurds, and we do business with them” – but “the entire family considers itself Turkmen, including my extended family.”

So why would he claim a Kurdish identity? “He said that because he was a humanitarian. Or maybe we have relatives who are Kurds, and that’s why Selahaddin thought that. This was how he defied the Turkish state,” Gulay said.

Gamze still has her doubts about her family’s origins. “I have asked my mother, my relatives many times, but they claim very clearly that they know where they come from, and they therefore believe they are Turkmen,” Gamze said. “But of course, I suspect that we could be Kurds.”

Selahaddin’s ethnic identity may have tested ties with some of his relatives, but one nephew is so proud of his connection to the doctor that he wants to be known as Omar Rastgeldi. Now a retired banker, Omar was close to his maternal uncle towards the end of his life, visiting him twice in Sweden in the 1980s. Omar, whose father was a retired judge of Turkey’s supreme court, is aware of the complexity of the debate around Selahaddin’s Kurdishness.

“This issue is sensitive,” Omar told Rudaw English, asserting that his uncle's ethnicity "doesn't make a difference" to his devotion to the rights of Kurdish people.

Omar recalls that Selahaddin “insisted” he was Kurdish in their correspondence. He is certain about where he stands on his uncle’s ethnic identity.

“I am on his side,” Omar said.

Jamal Alamdar, the engineer from Erbil who had been friends with Selahaddin for over two decades, said he was sure of the doctor's Kurdishness no matter the doubt that had been cast. Sometime in 1966, Jamal and a number of other Kurds were at a gathering in Selahaddin’s house; among them was Selahaddin’s younger brother Kemal, who spoke Turkish. “I asked him why he didn’t speak Kurdish,” Jamal recounted to Rudaw English. “I’m not Kurdish,” Kemal snapped at Jamal. “What about Selahaddin? He says he’s Kurdish,” Jamal persisted. “That's his business,” Kemal responded.

Kemal had arrived in Sweden four years after his older brother, and would eventually work as an engineer for telecommunications company Ericsson. "I followed in his footsteps that led me to settle in Sweden, where I remained and worked until retirement at the age of 65," Kemal said.

Like Gulay, Kemal – now 92 years old – explains his brother’s connection to Kurds as one influenced by his early surroundings. “Selahaddin spent his early childhood in Urfa and our village Tulmen, where he had the time to play with the Kurdish children and learn their language,” Kemal told Rudaw English in August. “All our relatives identified themselves as Turks and spoke Turkish at home.”

Over the course of the 1970s and 80s, Selahaddin would continue to establish warm connections with diaspora Kurds. He became acquainted with Abdul Rahman Qassemlou, a professor of economics in Paris and future leader of Kurdish liberation in Iran.

"He was very happy whenever Dr. Qassemlou and I visited him. For example, when my wife and I returned to Sweden in May 1985, after the years in the mountains of Kurdistan... we had lost our apartment in Stockholm and we were looking for a home," Sheikhmous recalled. "He had a big, nine-room apartment. He was willing to share the apartment with us and divide it into two."

Omar the banker visited Selahaddin twice in Stockholm, in 1981 and 1983, spending a total of one month with him. Omar found Selahaddin to be of good humour and in “very good health”.

The two would converse for hours at a time, and one particular issue kept rearing its head. Selahaddin’s citizenship was revoked by the Turkish authorities in the late 1960s, following a scathing report by a journalist from Milliyet newspaper about the doctor's work in promoting Kurdish rights.

While Gulay thinks Selahaddin was stripped of his citizenship because he skipped out on his obligatory military service, Omar believes that there were other factors in play.

“My uncle told me that the British government had put pressure on the Turkish government to take measures against him,” Omar recalls clearly of a conversation he had with Selahaddin about his Amnesty report on the treatment of Yemeni prisoners by the British government.

Selahaddin managed to visit Turkey on a handful of occasions after his citizenship was revoked, including a 1980 trip to see his gravely ill father. It is unclear if his visits to Turkey after his citizenship was revoked were conducted legally or illegally, but they were far less frequent than he wanted them to be.

“He loved Turkey so much and… he was very eager to come to Tulmen, to our village and he could not come,” Omar said.

Selahaddin once had close contacts with Turkish diplomatic representatives in Sweden, but by the 1980s, he would increasingly be shunned by the embassy staff.

“When we went there [to Sweden] to see him, there were always friends, but the Turkish circle was not there. There were some Kurdish friends, but there were very few Turkish friends around him,” Gamze recalled. “The embassy shunned him and he was totally isolated.”

Selahaddin hoped to be able to keep campaigning on the Kurdish issue, and maintain close ties to the Turkish establishment in Sweden – a task that became increasingly difficult as his stature grew amongst the Swedes and the country's Kurdish community.

“Once I went to see him [in his office], and as I entered, he ushered me into a room and locked the door from the outside,” Jamal recalled. Around half an hour later, the door opened. “Sorry, the Turkish ambassador was here,” Selahaddin told Jamal apologetically. Angered by the episode, Jamal asked Selahaddin not to invite him over when the ambassador was present.

“He wanted to have cordial relations with the Turkish embassy and do Kurdayati [campaign on Kurdish rights] too, but that was not possible,” Jamal told Rudaw English in August.

Hope that Selahaddin and other Kurds may have had for change to be enacted through official channels was dulled further when Turkey once again fell under the yoke of generals in 1980. Young Kurds in the country led an armed rebellion in the early 1980s, almost eliminating the possibility of vocal diaspora Kurds like Selahaddin being allowed back.

Selahaddin never married, but he did have a daughter from a Swedish partner.

"His life was intertwined with the Kurdish cause," Selahaddin’s daughter Vivian Alexandersen, a teacher in Norway, told Rudaw English.

Because of her parents’ acrimonious relationship, Vivian only became acquainted with her father as an adult.

"When Selahaddin contacted me in 1980, I was shocked to hear from him. My mother was very angry with Selahaddin, but he was a good human being… he was very smart, generous, humane, and Urfa was always in his mind," Vivian said. "He utterly detested the fact that the Turks treated the Kurds badly."

In February 1986, two Swedish detectives arrived at Vivian’s house in Norway to question her about her father’s connection to the assassination of his friend Olof Palme.

“They wanted to know if my father had a gun,” Vivian told Rudaw English. She assured the detectives that her father had not been armed. Chief Investigator Hans Holmer was driven by conspiracy theories, and blamed the Kurds for Palme's assassination, but produced no evidence to back up his claim.

Jamal too was also questioned by the Swedish authorities about Palme’s death.

"I was in London when they [Swedish police] called me and asked if I knew who was behind the assassination," Jamal told Rudaw English. "I said I didn't know who was behind it, but I knew who wasn’t: the Kurds. He [Palme] was a good friend of the Kurds.”

For Selahaddin, the world revolved around his birthplace of Urfa, so he was deeply affected by the obstacles that would limit his return home, Alakom recalled in 2016 during a seminar at the Kurdish Library in Sweden. In what was the next best thing, Selahaddin would record himself singing Urfa folk songs on cassettes and send them to his family. “I didn’t go, but don’t be upset brother, let my voice travel [to Urfa],” Selahaddin told his friend.

Despite his frequent absence, Selahaddin still sought to set the memory of his city in stone. In the 1950s, he invited Professor Judah Segal to Urfa, known in Latin as Edessa. Segal visited Urfa four times, according to Sinem Rastgeldi, one of the doctor’s many extended relatives who continue to live in the city, and wrote Edessa ‘The Blessed City’. Selahaddin left a lasting legacy on his hometown, where Sinem says he is still held in high regard.

Almost everyone Rudaw English spoke to for this piece believed that his exile from Urfa played a critical role in throwing Selahaddin into a bout of depression and heavy drinking that would last until the end of his life.

Gulay was in Mersin with her husband when she was awoken at 4 am on March 10, 1986 by the ringing of a telephone. “Your brother has contracted pneumonia,” she was told by the caller. Gulay and other relatives hurriedly began to arrange a trip to Sweden, but a second phone call brought their plan to a screeching halt. Selahaddin had a heart attack, and was pronounced dead just 12 days after his friend and chess partner Palme was assassinated.

The Turkish authorities did not want Selahaddin’s body to be buried in his country of birth, but a family member used his connection and influence to fly him back four days later. The body arrived in Istanbul airport to heavy police presence, then placed on another flight to Adana.

Gulay was too grief-stricken to go to Adana airport. Instead, her two sisters and Kemal went to receive the body.

“The early and sudden death of Selahaddin was a great misfortune and shock for me. He helped me in every way and in all stages of my life,” Kemal told Rudaw English via email.

Selahaddin’s natural resting place would have been Urfa. Instead, he is buried in Mersin, 440 kilometres away from his beloved birthplace. “He would have loved to have been buried in Urfa,” Gulay said. “But we could not risk the hassle.”

“Selahaddin was very connected to his roots,” his nephew Omar said. “He used to talk about his childhood and his youth in Tulmen. He wanted to be able to walk around the village and sit under the pistachio trees once more.”

Editing by Shahla Omar

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment