This is the final part in our four-part series on the history of Kurdish cinema. Part three is available here.

The majority of today’s successful Kurdish directors learned their craft in other lands, some in Iran, but most in Europe, some with formal education in cinema, others self-taught.

Collectively they have stories to tell the world with a burning desire to be heard and a passion that exceeds the artistry of the medium. As a result, one can hardly watch a Kurdish film and not shed a tear.

The Kurdish filmmaker in essence is the ambassador of his/her people, opening a window to the world through which one can get a glimpse of the daily life, history, culture, and the suffering of the Kurds. As film critic, David Rooney, in a Variety review of “Jiyan” states, “Jiyan gives a human face to the massacre [of Halabja].”

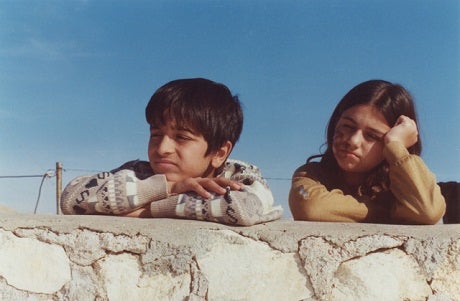

Jiyan (Pisheng Berzinji) and Sherko (Choman Hawrami) in "Jiyan", the first KRI region Kurdish film to receive international attention by Jano Rosebiani (2001) - Evini Films

Being the face and the voice of a nation are the driving force behind the passion for the cinematic art in Kurdistan.

Aside from shooting in Kurdistan, many have also seen success in turning out films in cross-cultural settings in diaspora, some with Kurdish subject matters, such as Hisham Zaman’s “Winterland” (2007), a Kurdish love story set in Oslo, Norway; Hiner Saleem’s “Vive la Mariée… et la Libération du Kurdistan” (1998), a romantic comedy about arranged marriage set in Paris; and Sahim Omer Kalifa’s “Zagros” (2018) about a Kurdish woman finding refuge in Brussels after being accused of adultery.

Other films involve non-Kurdish stories, such as Saleem’s “Beneath the Rooftops of Paris” based on true events during the heatwave that perturbed many of the elders of that city; my debut feature “Dance of the Pendulum” (1995), a parody of Hollywood B movies set in the Hollywood Hills, California; and most recently, Karzan Kader’s “Trading Paint” (2019) about a racecar driver starring John Travolta. Inversely, in “Chaplin of the Mountains” (2013) I brought foreign actors to Kurdistan, where Kurdish, American, and French characters roam the Kurdistan countryside.

As for films on Kurds by other than Kurds, “Zaré” by Soviet Armenian director Hamo Beknazarian (also known as Hamo Beknazarov and Amo Bek-Nazaryan) (1927) tops the list.

"Zare" (played by Maria Tenaz) the first Kurdish film ever, by Hamo Beknazarian made in Tblisi, Georgia (1926)

In the first installment of this series I identified “Yol” as being the first Kurdish film to gain international recognition (Cannes, 1982) albeit being in Turkish language. “Zaré” actually carries the title of being the very first Kurdish film.

It was made in the silent screen era in Tbilisi, Georgia. It depicts a Kurdish Yazidi love story between Zaré (Maria Tenaz) and Seydo (Herashia Nersisyan) who struggle for their right to a happy life.

“Zaré” was followed by another silent film, “Kurds-Yazidis” (1933) by Amasi Martirosyan about the establishment of a collective farm in a Kurdish village in the Soviet Armenia. Both films are preserved at the National Film Archives of Armenia.

There have also been a handful of films about Kurds in Iran in the 1960s and onward, among them “Dalahoo” (Siyamak Yasami, 1967), lensed in the Dalaho mountain of Kermanshah.

Other films include “Sadeq The Kurd” (Naser Teghvari, 1972), “Abu Jasim the Lor”, “The Kurdish Girl”, “Husain the Kurd”, and “Kurdistan Horsemen.” These films, like most other films out of Middle East, are either cheap thrills, B-movie actioners, or inflated melodramas.

The most peculiar among them is the Bollywood flick “The Lor Girl” (1933) lensed in Bombay by Khan Bahadur Ardashir Irani. It depicts the Kurdish province of Loristan as a place of thugs and robbers.

Interestingly, although made in India, “The Lor Girl”, also known as ‘The Iran of Yesterday and the Iran of Today’, was the first sound film ever to be produced in the Persian language.

Contrary to those early B-movies, more recent arthouse Iranian films of the past two decades place Kurds in a better light, such as Abbas Kiarostami’s “The Wind Will Carry Us” (1999) and Samira Makhmalbaf’s “Blackboards” (2000) among others.

As for films from the West, aside from occasional television documentaries, the only feature film that surfaces is Germany’s “Wild Kurdistan” (Franz Josef Gottlieb, 1965) - a war actioner that builds on exoticism and parades Kurds and other oriental groups of the Ottoman Times/WWI era as what the title alludes to.

Meanwhile Kurd artists have contributed a good deal to the cinemas of the ruling states, especially in Iraq and Turkey. Despite not owning a cinema industry of her on, Iraqi Helmers have had their share in spewing melodramas of their own along with a few propaganda pics.

A handful of the films were produced by Kurds in the 1960s and 70s, albeit in Arabic and with no relation to Kurds – as Kurdish art and literature was commonly suppressed by the Baath regime.

Among the films spawned by Kurds are “The Rose” (Yahya Faiq, 1956); Kamiran Husni’s “Saeed Afandi” (1957) and “The Marriage Project” (1960); Hikmet Labeeb’s “Basra at 11 O’clock” (1963) and “Autumn Leaves” (1964); and Abduljabar Wali’s “Regret” (1954) among others.

Notwithstanding, there were also some attempts at Kurdish production, such as Yahya Faiq’s flirt with the saga of “Mem and Zin” and a film about the legendary “Kawa, the Blacksmith” by Georgis Yusif. However, neither of the films came to fruition due to road blocks by the regime.

Other films worthy of note made in the dawn of Kurdish cinema are the award-winning “A Song for Beko” (Nizamettin Aric, 1992) lensed in Armenia, and “Tunnel” (Mahdi Omed, 1993), made in Tajikistan.

In Turkey as well many of the homegrown films of the past century were helmed by Kurds and Kurdish films had to be made in the Turkish language. Filmmakers included Yilmaz Guney, Yilmaz Arsalan, and Serif Goren among innumerous others.

Today many if not most Kurdish films of the North continue to be recorded in Turkish for discernible reasons, and only those in exile have the luxury of using their mother tongue in their motion pictures without getting into hot water. However, for reasons inexplicable, some diaspora directors continue to script and record their films in Turkish.

Another astounding fact is that a few of our colleagues from various regions of Kurdistan avoid presenting their works with the Kurdistan label in spite of being financed by and produced in Kurdistan. Though their reasoning is often related to marketability, I find it bewildering, inexplicable, and inexcusable.

I find it imperative to close this segment and my take on the short history of Kurdish cinema series with an issue I faced in 2015. When the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) selected “One Candle, Two Candles” as a runner for the Golden Globe Award, they listed it as an Iraqi film. I struggled to have that changed to a ‘Kurdistan selection’ and after considerable back and forth they agreed to the change.

By doing this I am in no way being anti-Iraq, but rather giving my work its righteous identity. In fact all films made in the Kurdistan Region, mine included, are listed as Iraqi films on Wikipedia, and appropriately so, but as Kurd filmmakers representing an oppressed nation it is crucial that we stand cool-headed, for promoting the Kurdish identity is one with, and inseparable from, promoting our right to live as a distinctive nation.

The majority of today’s successful Kurdish directors learned their craft in other lands, some in Iran, but most in Europe, some with formal education in cinema, others self-taught.

Collectively they have stories to tell the world with a burning desire to be heard and a passion that exceeds the artistry of the medium. As a result, one can hardly watch a Kurdish film and not shed a tear.

The Kurdish filmmaker in essence is the ambassador of his/her people, opening a window to the world through which one can get a glimpse of the daily life, history, culture, and the suffering of the Kurds. As film critic, David Rooney, in a Variety review of “Jiyan” states, “Jiyan gives a human face to the massacre [of Halabja].”

Jiyan (Pisheng Berzinji) and Sherko (Choman Hawrami) in "Jiyan", the first KRI region Kurdish film to receive international attention by Jano Rosebiani (2001) - Evini Films

Being the face and the voice of a nation are the driving force behind the passion for the cinematic art in Kurdistan.

Aside from shooting in Kurdistan, many have also seen success in turning out films in cross-cultural settings in diaspora, some with Kurdish subject matters, such as Hisham Zaman’s “Winterland” (2007), a Kurdish love story set in Oslo, Norway; Hiner Saleem’s “Vive la Mariée… et la Libération du Kurdistan” (1998), a romantic comedy about arranged marriage set in Paris; and Sahim Omer Kalifa’s “Zagros” (2018) about a Kurdish woman finding refuge in Brussels after being accused of adultery.

Other films involve non-Kurdish stories, such as Saleem’s “Beneath the Rooftops of Paris” based on true events during the heatwave that perturbed many of the elders of that city; my debut feature “Dance of the Pendulum” (1995), a parody of Hollywood B movies set in the Hollywood Hills, California; and most recently, Karzan Kader’s “Trading Paint” (2019) about a racecar driver starring John Travolta. Inversely, in “Chaplin of the Mountains” (2013) I brought foreign actors to Kurdistan, where Kurdish, American, and French characters roam the Kurdistan countryside.

As for films on Kurds by other than Kurds, “Zaré” by Soviet Armenian director Hamo Beknazarian (also known as Hamo Beknazarov and Amo Bek-Nazaryan) (1927) tops the list.

"Zare" (played by Maria Tenaz) the first Kurdish film ever, by Hamo Beknazarian made in Tblisi, Georgia (1926)

In the first installment of this series I identified “Yol” as being the first Kurdish film to gain international recognition (Cannes, 1982) albeit being in Turkish language. “Zaré” actually carries the title of being the very first Kurdish film.

It was made in the silent screen era in Tbilisi, Georgia. It depicts a Kurdish Yazidi love story between Zaré (Maria Tenaz) and Seydo (Herashia Nersisyan) who struggle for their right to a happy life.

“Zaré” was followed by another silent film, “Kurds-Yazidis” (1933) by Amasi Martirosyan about the establishment of a collective farm in a Kurdish village in the Soviet Armenia. Both films are preserved at the National Film Archives of Armenia.

There have also been a handful of films about Kurds in Iran in the 1960s and onward, among them “Dalahoo” (Siyamak Yasami, 1967), lensed in the Dalaho mountain of Kermanshah.

Other films include “Sadeq The Kurd” (Naser Teghvari, 1972), “Abu Jasim the Lor”, “The Kurdish Girl”, “Husain the Kurd”, and “Kurdistan Horsemen.” These films, like most other films out of Middle East, are either cheap thrills, B-movie actioners, or inflated melodramas.

The most peculiar among them is the Bollywood flick “The Lor Girl” (1933) lensed in Bombay by Khan Bahadur Ardashir Irani. It depicts the Kurdish province of Loristan as a place of thugs and robbers.

Interestingly, although made in India, “The Lor Girl”, also known as ‘The Iran of Yesterday and the Iran of Today’, was the first sound film ever to be produced in the Persian language.

Contrary to those early B-movies, more recent arthouse Iranian films of the past two decades place Kurds in a better light, such as Abbas Kiarostami’s “The Wind Will Carry Us” (1999) and Samira Makhmalbaf’s “Blackboards” (2000) among others.

As for films from the West, aside from occasional television documentaries, the only feature film that surfaces is Germany’s “Wild Kurdistan” (Franz Josef Gottlieb, 1965) - a war actioner that builds on exoticism and parades Kurds and other oriental groups of the Ottoman Times/WWI era as what the title alludes to.

Meanwhile Kurd artists have contributed a good deal to the cinemas of the ruling states, especially in Iraq and Turkey. Despite not owning a cinema industry of her on, Iraqi Helmers have had their share in spewing melodramas of their own along with a few propaganda pics.

A handful of the films were produced by Kurds in the 1960s and 70s, albeit in Arabic and with no relation to Kurds – as Kurdish art and literature was commonly suppressed by the Baath regime.

Among the films spawned by Kurds are “The Rose” (Yahya Faiq, 1956); Kamiran Husni’s “Saeed Afandi” (1957) and “The Marriage Project” (1960); Hikmet Labeeb’s “Basra at 11 O’clock” (1963) and “Autumn Leaves” (1964); and Abduljabar Wali’s “Regret” (1954) among others.

Notwithstanding, there were also some attempts at Kurdish production, such as Yahya Faiq’s flirt with the saga of “Mem and Zin” and a film about the legendary “Kawa, the Blacksmith” by Georgis Yusif. However, neither of the films came to fruition due to road blocks by the regime.

Like their Iranian and Turkish counterparts, the Iraqi titles in general were no ground-breakers. They are rather over-acted parochial melodramas.

Other films worthy of note made in the dawn of Kurdish cinema are the award-winning “A Song for Beko” (Nizamettin Aric, 1992) lensed in Armenia, and “Tunnel” (Mahdi Omed, 1993), made in Tajikistan.

In Turkey as well many of the homegrown films of the past century were helmed by Kurds and Kurdish films had to be made in the Turkish language. Filmmakers included Yilmaz Guney, Yilmaz Arsalan, and Serif Goren among innumerous others.

Today many if not most Kurdish films of the North continue to be recorded in Turkish for discernible reasons, and only those in exile have the luxury of using their mother tongue in their motion pictures without getting into hot water. However, for reasons inexplicable, some diaspora directors continue to script and record their films in Turkish.

Another astounding fact is that a few of our colleagues from various regions of Kurdistan avoid presenting their works with the Kurdistan label in spite of being financed by and produced in Kurdistan. Though their reasoning is often related to marketability, I find it bewildering, inexplicable, and inexcusable.

I find it imperative to close this segment and my take on the short history of Kurdish cinema series with an issue I faced in 2015. When the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) selected “One Candle, Two Candles” as a runner for the Golden Globe Award, they listed it as an Iraqi film. I struggled to have that changed to a ‘Kurdistan selection’ and after considerable back and forth they agreed to the change.

By doing this I am in no way being anti-Iraq, but rather giving my work its righteous identity. In fact all films made in the Kurdistan Region, mine included, are listed as Iraqi films on Wikipedia, and appropriately so, but as Kurd filmmakers representing an oppressed nation it is crucial that we stand cool-headed, for promoting the Kurdish identity is one with, and inseparable from, promoting our right to live as a distinctive nation.

Jano Rosebiani is an American-Kurdish scriptwriter, director, producer, and editor associated with Kurdish New Wave cinema. This is the third part of a four-part series about the history of Kurdish cinema. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Rudaw. |

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment