Young men walk amid the destruction in Afrin in March 2018, after Turkish-led forces entered the city. File photo: AFP

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — When civil warfare struck Aleppo in 2012, Manan* returned to his village of origin in Afrin, northwest Syria, with his wife and young children in tow. Miles away from embattled Aleppo, there was relief: they thought they were returning to safety.

But a different war followed them home.

The family, living in a village whose name is not disclosed to protect them from reprisals, are part of Afrin’s fast shrinking Yezidi minority under target by Turkish-backed Syrian armed groups.

“We live in constant fear,” Manan told Rudaw English via telephone. “Since I’ve returned to my village, I’ve become sick with stress. If a car comes, I’m afraid.”

Controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) since 2012, after the previous year’s Syrian uprising, the Turkish army and Ankara-backed Syrian proxy groups invaded Afrin in January 2018, ruling the area ever since. Once home to several minorities, including Christians, Kurds and Yezidis, human rights monitors raised the alarm of various abuses against minority groups - but not before countless accounts of kidnap, forced conversion, looting and abuse seeped out from the city.

Yezidis are no stranger to persecution, counting 74 genocides against them throughout their history in the Middle East – from the hands of the former Ottoman Empire in modern-day Turkey, to the Islamic State (ISIS) in Iraq. Now, Turkish forces and their proxies are pushing the last of what was once a community of tens of thousands of Yezidis out of Syria.

They are not the only ones to suffer at the hands of Turkey and the armed groups it supports. Operation Peace Spring, launched in October of 2019 to clear a swathe of the country’s north, saw the mass displacement of the area’s minority groups, among them Yezidis. In the neighbouring Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Ankara’s regular airstrikes on border towns have emptied Assyrian as well as Kurdish villages.

“It is clear that when they [Turkey] invade and occupy territory, they take away religious freedom and commit atrocities against Yezidis, Christians, Kurds, and other minority communities,” Nadine Maenza, a commissioner and vice chair of the United States Commission for International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) told Rudaw English.

Life in Afrin, an area once best known for its olive trees, is a far cry from the peaceful childhood Manan remembers. Now, he rarely travels into town for fear of being caught in bombings that regular shake the city. In the past two years, churches have been torched and emptied, and Yezidi graves desecrated in the city where Manan says “even the dead can’t find peace.”

In May, activist Nadia Murad, who survived Yezidi genocide in Iraq at the hands of the ISIS, warned that proxy groups were “ethnically cleansing” Afrin of the ethnoreligious minority. Afrin’s Yezidis have drawn parallels to the genocide of their bretheren in Iraq, and worry that the same fate awaits them.

“We are scared that what happened in Shingal will happen to us. That is our biggest fear,” Manan added.

In an alarming echo of the fate that befell Iraq’s Yezidis six years ago, at least six Yezidi women were kidnapped in the district from October 2019 to April of this year.

“Every day they expect that they will be banished from their homes and towns by the militants, kidnapped for ransom, or have their crops and land confiscated. Some Yezidis are hiding their religion to protect themselves,” Nisan Ahmado, a Yezidi journalist from Afrin now based in the United States told Rudaw English.

Ahmado’s grandmother was the last of her family to remain Busofan, the largest of 22 Yezidi villages once dotted around the district. When Turkish-backed militants arrived in the village in 2018, she was ordered to leave her home, but died in her sleep before the order could be carried out.

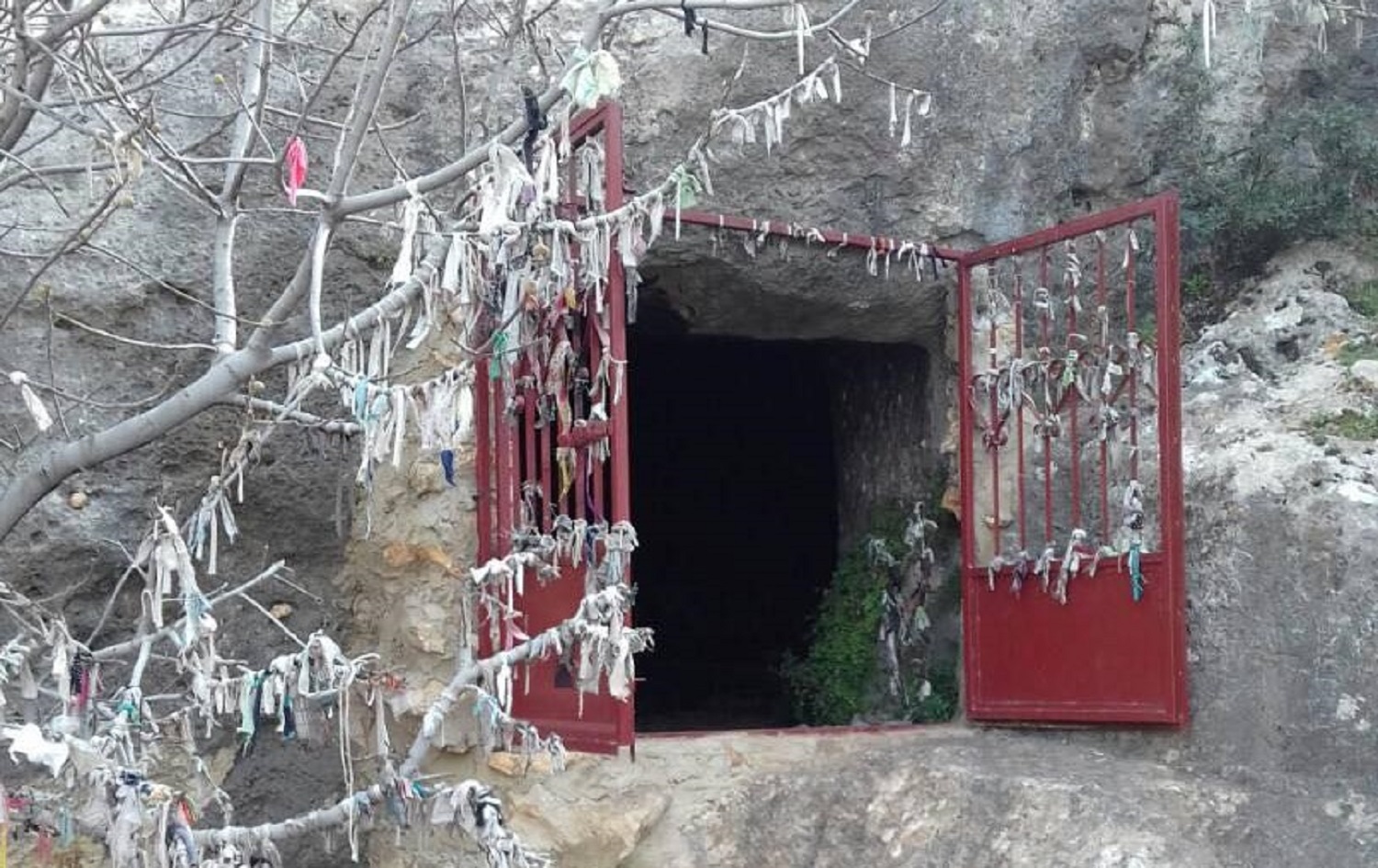

Before the invasion, Afrin’s Yezidis openly celebrated the festivals so central to their faith. In Spring, they commemorated Sere Sale, or Yezidi New Year, typically welcomed with bright eggs and large celebratory crowds. In AFP footage filmed before the incursion, locals climb to a Yezidi temple surrounded by trees decorated with coloured cloths. Oil lamps line the temple’s interior, visitors kissing the walls and muttering in quiet prayer.

Unlike Islam, Christianity and Judaism, the Yezidi religion is not officially recognised by the Baath regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. According to Ahmado, greater freedoms came to Afrin with the 2012 arrival of the SDF’s People’s Protection Units (YPG), the leading military group in Kurdish-held areas of northeast Syria otherwise known as Rojava.

“Before the occupation of Afrin, and during the time when the SDF controlled the area, Yezidis enjoyed the freedom of belief, they practiced their rituals, and their holy places were honored and rebuilt, their holidays and way of life were celebrated,” Ahmado said.

US officials have argued that Rojava, under the control of the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria (AANES), is the last safe haven for the community in the war-torn country.

“AANES-governed areas are the only place in Syria where the Yezidi community can thrive,” said Maenza.

Now, holiday wishes are said in quiet passing, feasts observed within the confines of the home.

“Before the invasion, Yezidis celebrated in an open way,” Manan said. “Now holidays are just greetings...we can’t even say we are Yezidi.”

It is not the world into which he wished to welcome his unborn child, due in the autumn.

“My wife is delighted about the pregnancy, she has been waiting for nine years..but the circumstances are not right. We want to return to Aleppo, so they [the children] can complete their studies and lead a life free from fear and terrorism.”

Like the rest of Syria, Afrin is bowing under the pressure of a crippled currency that has sent the cost of basic goods soaring. The price of a bag of bread has shot up to at least 1,000 Syrian pounds, five times its pre-war price.

“We can only afford to buy vegetables,” Manan added.

Uncertain exile

Father-of-two Mofeed is one of many Yezidis who has sought refuge beyond Syria. Like Manan, he moved to Aleppo as a teenager, where jobs were once plentiful. In 2012, however, he headed to the Lebanese capital of Beirut.

Seeking only a temporary stay in Lebanon, Mofeed did not apply for asylum, so he works illegally at a flower shop for the equivalent of $100 a month.

Yezidis have sought refuge across Lebanon, from Beirut to Tyre in the south. But like Syria, the country is being tightly squeezed by a financial crisis that has spiraled since protests erupted in October 2019.

Life is growing ever more difficult for Mofeed and his family; his daughter needs nasal surgery costing $1,500, a price far beyond his reach as the cost of even the most basic of goods soars. But returning to Afrin, where his mother still lives, is not an option.

“If we go back to Afrin now, our lives will be even worse. We have a lot of shrines, and they destroyed all of them. How is it possible to go back and live with those people?”

As Lebanon falls further into economic strife, and Afrin shows little sign of peace, he is looking further afield for a brighter future.

“We want to go somewhere where our human rights are preserved.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

Editing by Shahla Omar

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment