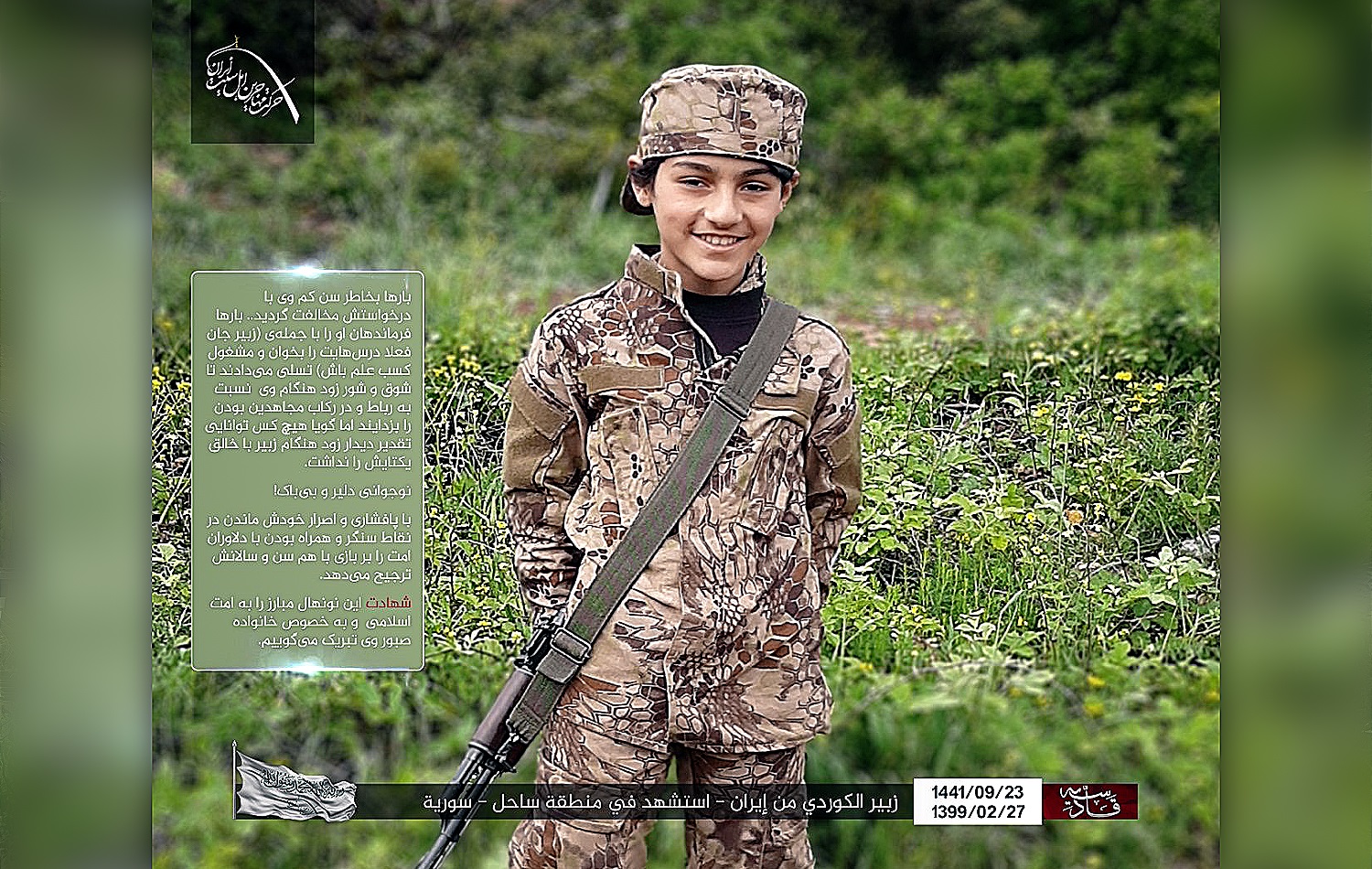

Iranian Kurdish jihadist Zakaria al-Kurdi was killed fighting in the Sahel area of northwest Syria on August 5, 2019. Photo via jihadist media outlet al-Qadissiya on Telegram

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — Zakaria sat at an outpost framed by olive trees on one of the bloodiest frontlines in Syria, full combat gear weighing down his slender body. His close friend Faruq had unexpectedly joined him. An Arab fighter was meant to man a stretch of front line with Zakaria that cold morning in January 2019, but he fell ill, and Faruq volunteered to replace him. The two began to sing a nasheed, an Islamic recitation, as they gripped their guns in anticipation of battle.

Zakaria and Faruq were foreign jihadists in Sahel, an area cutting across embattled northwest Syria’s Latakia and Tartus governorates. They had travelled thousands of kilometers from the Kurdish region of Iran, where four decades of ethnic and religious discrimination has left the local population bitter about Shiite theocratic rule. Thousands of young, Sunni, Kurdish men from Iran have sought solace in carrying out religious warfare, or jihad, in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and beyond.

A whistling sound floated through the air, followed by an explosion. A mortar had landed.

“I fell to the ground, and Faruq fell on top of me,” Zakaria recalled in an interview published by a jihadist group. “The mortar shrapnel pierced Faruq’s chest and his heart. Blood was pouring out of his body.”

Zakaria was rushed to a hospital. He came to, devastated by the death of his friend. The same fate soon befell him; he was killed in Sahel on August 5, 2019.

Kurds have been a critical part of the international, ongoing fight against the Islamic State (ISIS) and other terrorist groups in Syria and Iraq. But a smaller current of Kurds have travelled to these two countries over the years to perform their religious duty of jihad, on the side of ISIS, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly the Nusra Front), and other groups.

More than a year after the territorial end of the ISIS caliphate in Syria, tens of thousands of international jihadists are still fighting on the front lines of Idlib, in the northwest of the country. Their equally international adversary is the mostly Shiite jihadists recruited by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), from Iran, Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan, fighting on behalf of Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad.

In what could trigger yet another humanitarian catastrophe, Syrian regime and Russian forces are gearing up to take control of the HTS-controlled area, home to at least three million people living under extreme economic hardship.

The lines of impending takeover have not yet been drawn, but the scatter of the militants who inhabit the area could have untold international security consequences, independent Syria and Levant analyst Sam Heller told Rudaw.

“If Idlib devolves into chaos, and some large, uncontrolled mass of people flees across the border, some of these militants could escape and then travel onwards from Turkey,” Heller said. “In terms of international security, then, it's possible that eliminating this Idlib pocket may actually be more dangerous than attempting to contain it.”

“With many of these groups, the main threat seems less to be that they will direct attacks from inside Idlib, more that they will manage to leave Idlib and reach somewhere else, where they could have an outsized destructive impact.”

There is no exact number on how many Kurdish jihadists are currently based in and around Idlib, but one jihadist source well connected in both Iran and Idlib told Rudaw English that the number could be as high as 3,000. However, this figure may be exaggerated, with jihadi groups prone to inflating figures for propaganda purposes.

An online trove of Kurdish jihadism

Rudaw English has managed to access a cache of digital data including announcements, pictures and videos which shows that there are two jihadist groups operating in the Idlib area in which Kurds hold top-tier positions. The materials indicate that around two dozen Kurdish jihadists from Iran have lost their lives on the battlefield in recent years. Zubair al-Kurdi was the last Kurdish jihadist to be killed, on May 16. He appeared to be of no more than 12 years of age.

Kurdish fighters can be seen using heavy artillery and guns on the front line, as well as vehicle-borne IEDs. One fighter, Abdullah al-Kurdi, carried out a devastating VBIED attack against regime forces on December 24 in the south of Idlib. The drone-filmed attack was exemplary enough to be turned into a propaganda video by the HTS.

Guided by the digital materials, Rudaw’s investigation in the Kurdish area in Iran has revealed that the group has actively promoted jihad, and continues to recruit many young Kurdish men to the battlefields of Syria.

These Iranian Kurdish jihadists once operated as part of the better known Ansar al-Islam group, a sophisticated and independent Kurdish jihadist group that has repeatedly refused to come under the yoke of the international jihad ringleader al-Qaeda. Ansar al-Islam was founded sometime in late 2001 and gained infamy when they soon established the Byara Emirate, a mini Islamic state in the highlands of the Hawraman region that straddles the Iraq-Iran border.

Faced in 2016 with assault from both ISIS and regime forces in northwest Syria, the Nusra Front rebranded as the Fath al-Sham Front, before merging with other groups to consolidate its power to form the HTS in January 2017.

Iranian Kurdish jihadists who had made the journey to Syria chose to fight under the Nusra umbrella, but retain their own name and structure. They operated as the “Movement of the Muhajerin of Iran’s Sunnis”, a mostly Kurdish group that also counted jihadists from the Arab, Turkmen, Gilaki and Balochis areas of the country among its ranks.

Zakaria and Faruq were among the Kurds who belonged to the Muhajerin.

The group pledged allegiance to Fath al-Sham head Abu Mohammad Jolani in July 2016, in a statement calling for unity among jihadist groups. The Muhajerin’s top mufti, or advisor, is Abdul Rahman Fattahi, an Iranian Kurd who began his journey to jihadism in the early 1990s.

Addressing a group of jihadists in April last year, Fattahi made clear his belief that sacrificial suicide was the ultimate religious duty – beyond any made even by the Prophet Mohammed’s sahaba, or original companions.

“What the Mujahedin [those engaged in jihad] are doing in our time be in Iraq, in Afghanistan or here in Sham [the Levant], though it is not greater than what the companions did, it is not less either,” Fattahi told a group of jihadists on April 2019. “What a suicide bomber does is like the sacrifices of 50 sahaba.”

Thanks to the spearheading of international jihadism for a time by Osama Bin Laden, “the Ummah [Muslim world-nation] has become great again, and jihad is no longer strange,” Fattahi said in Sahel in June 2019.

Fattahi’s course embodies how violent jihadist ideology spread in the Kurdish areas in Iran with the tacit approval of Iranian intelligence and paramilitary services, allowing Kurdish jihadism to become woven into a holy war of global proportions.

Fattahi’s forefather

Fattahi was shaped by Abdul Qader Tawhidi, an Iranian Sunni Kurd who studied in Halabja, Iraqi Kurdistan in the mid-1970s, then travelled across Kurdish areas of Iran to familiarize himself with its Islamist religious currents. The two became a near inseparable student–teacher duo in the 1990s who shaped Kurdish jihadism for decades to come.

Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution and the Soviet invasion of neighbouring Afghanistan had rekindled regional religious sensitivities. The revolution was initially met with hope by Islamists, who thought it may beckon the revival of an Islamic identity weakened under the Shah’s regime.

The concept of jihad and a state ruled by Sharia crossed sect, appealing to Sunni figures like Tawhidi as well as young IRGC guards and their Shiite masters including Ali Khamenei. As a young Shiite cleric imprisoned by the Shah’s regime for his activism, Khamenei began familiarising himself with Salafist, jihadist ideology in the early 1970s, translating their publications from inside prison. Other Shiite clerics and scholars read the work of jihadist theorists with fervour too – particularly the Egyptian Sayyid Qutb, whose writings became canon for the new revolutionary endeavour.

In what looked like it would beckon a new, pan-sect Islamist rule, revolution leader Ruhollah Khomeini said he wanted only to implement the doctrine of the Quran, while Khamenei was so moved by the concept of an Islamic nation that there was even talk of every revolutionary guard carrying a pocket-sized version of Qutb’s “Islamic Studies”, on the necessity to establish an Islamic state confronting the dominant world order. The book’s Persian edition title was altered to ask, “What are we saying?”

But three years of post-revolution negotiations between Iranian Sunni leaders including Tawhidi and members of the Shiite leadership led to no agreement. By the end of 1984, Tawhidi had announced the creation of the Islamic Movement for the Sunnis of Iran, in claimed defence of sect members in the country.

Meetings to resolve differences with Iranian government and intelligence officials a few months later also proved futile, and the then-burgeoning Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) went to war with guerilla Kurdish Sunni groups who rejected the regime. The IRGC’s top echelon, including the late Qasem Soleimani, honed their skills fighting the Kurds.

Authorities began arresting Tawhidi followers a few months later. The execution of three of the group’s top leaders led Tawhidi to declare jihad against the regime. Two other contemporary Kurdish Islamic movements, led by charismatic leaders Naser Subhani and Ahmad Moftizadeh, opposed the take-up of arms. Ironically, Tawhidi survived years of battle, while the other two leaders were killed at the hands of the IRGC.

Afghan volunteers trained at camps near Tehran were dispatched west by the IRGC to Hawraman, where they would gain the practical experience they needed before being sent back to Afghanistan to fight the Soviets. Afghan presence in an Iran-backed force foreran present-day clashes in northwest Syria between Fattahi’s followers on the one hand, and IRGC guards and their Afghan proxies on the other.

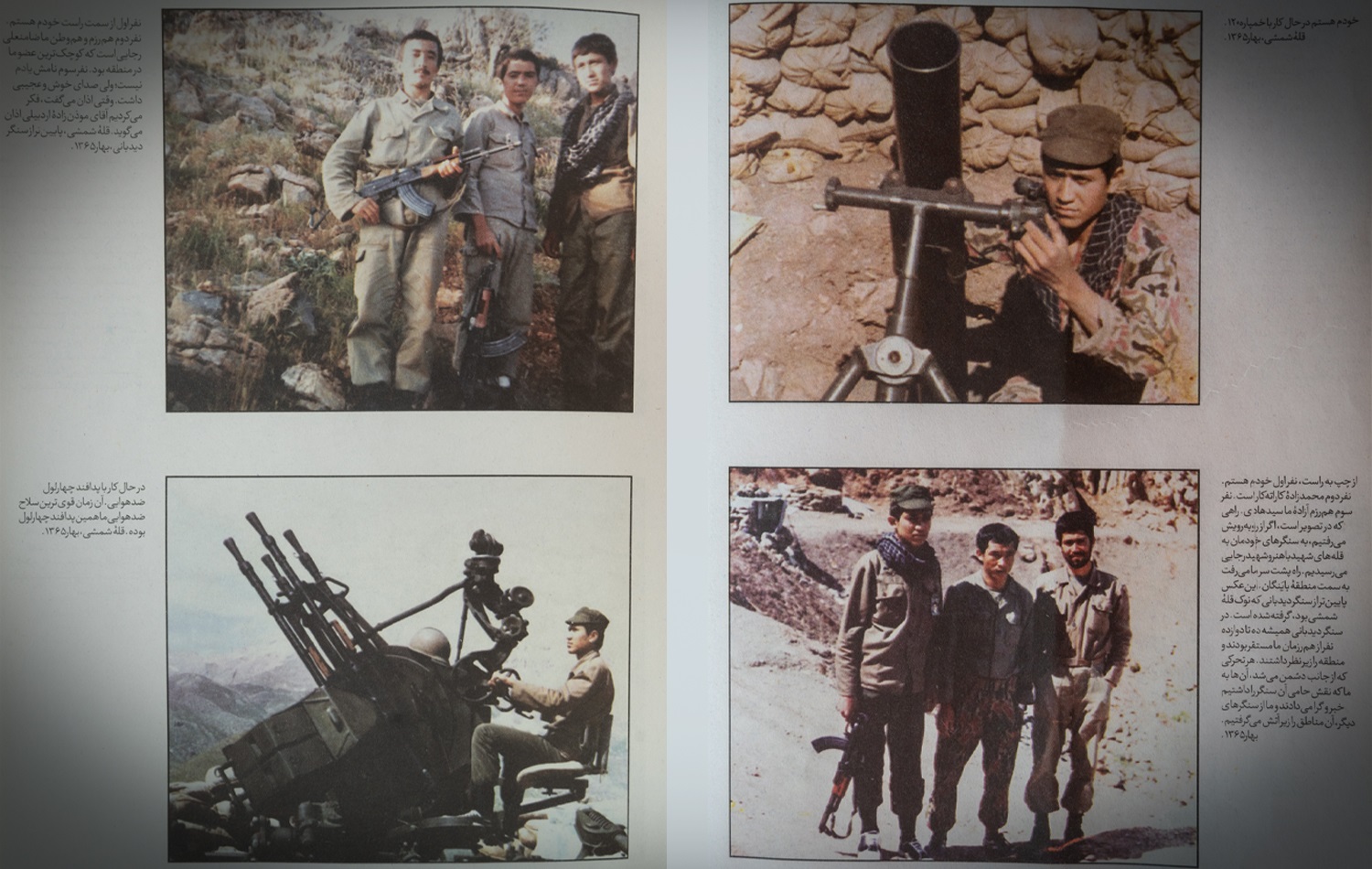

Surviving photos show teenage Afghans at the heights of Hawraman, captured both manning heavy machine guns and posing with flowers in hand.

Tawhidi continued fighting in the border area in Halabja from 1985 to 1987, when a crackdown by Saddam Hussein forced many top religious scholars, including Tawhidi’s teachers, to cross from Halabja into Iran. It was when the Kurds of Halabja concluded that armed struggle was needed to fight Saddam that the concept of jihad gained momentum there. Though the IRGC had no issues working with secular Iraqi Kurdish groups opposing Saddam, a number of commanders had for years visited Kurdish refugee leaders in western Iranian camps, trying to persuade them to set up a new group to fight in the name of Islam.

With IRGC support, Halabja became a gravitational centre for jihadism, where local subscribers to the movement and smaller jihadist groups were brought together to establish the Kurdistan Islamic Movement (KIM), fighting Saddam Hussein’s regime for two years before Iran withdrew its support from Kurdish opposition groups. It is not clear if the Halabja jihadists named their KIM group after that of Tawhidi, but what is certain is that Kurdish jihadists in Iraq and Iran remained close-knit.

After a 1991 uprising, Kurds were given their own semi-autonomous region, but the area soon descended into a war over resources between Iraqi Kurdistan’s two main parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), creating chaos conducive to more radical elements within the KIM to rise to the surface and demand more extreme measures against largely secular forces. KIM rifts deepened over whether the movement should partake in Iraqi Kurdistan’s democracy-building project.

Amid the tumult, a young Abdul Rahman Fattahi slipped across the border into Iraqi Kurdistan with a group of other students to complete his religious studies at a seminary in Ranya, at the foot of Qandil mountains. His future mentor Tawhidi had taken up refuge not far from the school, absorbed in resumption of his own religious studies.

“In the spring of 1993...we started our religious teaching…in Ranya in the religious school belonging to the Kurdistan Islamic Movement,” Fattahi recalled in an undated interview. “It was there that I got to know Mamosta (teacher) Abdulqader [Tawhidi]...he was living in a refugee camp and we were told that he was Iranian and knew what he was talking about...we’d go to him most Fridays for lessons and we were told that this teacher had been carrying out jihad in Iraqi Kurdistan and in the border area with Iran against the Iranian regime for a long time...he was teaching us about jihad and qital (killing).”

In Fattahi, Tawhidi found an eager student onto whom he could bestow jihadist ideology.

The duo had sought to avoid being dragged into the KIM’s quarrels with other parties. To gain public favour, the movement’s stalwart members felt obliged to hand over top positions to hotheaded, popular upstarts. Three main wings had emerged within the KIM, breeding a hostility that made life very difficult for its average jihadist.

The main wing was Benamala, or the Family, a group of shrewd Islamists led by KIM co-founder Osman Abdulaziz interested in partaking in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) project with the KDP and PUK.

Hotheaded young cleric Ali Bapir headed up a wing that came to be known as Komal. Bapir was notorious for having killed his own teenage brother who allegedly conspired with the Baath regime to kill a KIM fighter in the late 1980s. Though known to be a good commander, Bapir struggled to work within the framework set out by KIM strategists.

Leading the Islah wing was Mala Krekar, who had taught religious studies in Pakistan for two years in the 1980s where he met with jihadist figures such as Abdullah Azam and Osama Bin Laden. He became head of the KIM’s military wing and brought grand-scheme thinking to the movement, but was less adept as an administrator and team player, flitting between the frontlines and far-flung Norway where his family resided.

Strain between currents was so pronounced that Krekar confessed in a video years later that he had plotted against Abdulaziz to weaken the KIM in 1988, just one year after he joined the group.

It was amid these fractures that a group of jihadists who wanted to move away from the factionalism of the KIM and its nationalist Islamist project. The KIM’s hardcore elements, along with other smaller jihadist groups, came together to establish the now-infamous Ansar al-Islam.

One Ansar al-Islam contingent, Hezi 2 Soran, was particularly important in the establishment of a multi-ethnic, transnational brand of Kurdish-led jihadism.

Hezi 2 Soran: towards international jihadism

Hezi 2 Soran was a non-partisan group that maintained good relations with all three of the existing KIM currents, and its avoidance of factionalism would allow it to grow into a formidable force. The hardcore jihadist group was established in 1995, named after the Erbil province city where the KIM ran an important military academy following the 1992 establishment of the KRG.

Hezi 2 Soran bore historical grudges. It wanted to break free from dependence on arms from an IRGC that had stopped providing arms to the KIM when it fought the PUK in the early 1990s. They repaired old fighters’ guns for reuse, and established a publishing house for jihadist literature to broaden its reach.

A long-established principle in the KIM was that it be an exclusively Kurdish nationalist Islamic project, but Hezi 2 Soran provided training to Iraqi and Syrian Arab jihadists who sought it. In charge of communication with Arab jihadists was Abu Abdullah Shafei; his investment in Arab fighters would prove invaluable in the long term, facilitating Kurdish jihadist operation in the rest of Iraq for years to come.

The group expanded its horizons further when it began transnational communication with top jihadist scholars, and sent groups of fighters to Afghanistan for training. Kurdish jihadists sent delegations to Afghanistan to meet with Bin Laden, the main architect of international jihad in the late 1990s – but the only representative known to have given a pledge of allegiance to al-Qaeda was Tahseen Ali Abdulaziz, son of KIM co-founder Ali Abdulaziz.

The most radical of the KIM’s groups – Hezi 2 Soran, and two smaller factions, Tawhid and Hamas – came together to establish Jund al-Islam in September 2001. The group lasted around 100 days, before merging with Krekar's Islah to become Ansar al-Islam.

Ansar al-Islam took charge of Iraqi Kurdish Hawraman to establish the Byara Emirate, implementing a severe interpretation of Islamic penal code. They lashed and executed infidels, those who did not abide by their regime of terror. Fattahi was known to have been a frequent visitor to the project, but did not take part in fighting.

Byara Emirate: a testing ground

The emirate was the first time that Iraq’s jihadist Kurds were able to control territory and establish rule based on a strict interpretation of Sharia law, a rite of passage in the realisation of the ultimate goal – the Islamic caliphate.

Iranian Kurdish jihadists provided vital cross-border assistance in the Byara project. With the area under embargo by the PUK, Iranian Kurds set up critical networks that illegally provided sustenance to the area, and – crucially – aided and hosted the foreign fighters who wanted to join the emirate.

Several hundred Saudi, Iraqi, Syrian, Palestinian, and Jordanian foreign fighters were smuggled into Byara thanks to the assistance of Tawhidi’s Iranian Kurdish followers, Ansar fighter Mala Mohsin Khamzaei, alias Abu Zakaria, told Kurdish researcher Mokhtar Hooshmand in a 2011 interview.

Aided by Tawhidi’s followers and in sworn allegiance to Ansar's Shafei, one Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, future leader of an unprecedentedly bloodthirsty al-Qaeda in Iraq, arrived in Byara in early 2002. Shafei ordered secret Ansar cells to smuggle Zarqawi to Baghdad soon after, where he stayed in secret at the house of main local Ansar representative Haji Mustafa for a year. Haji Mustafa had introduced Zarqawi to Ansar members in Baghdad, but when his protector was detained, Zarqawi repaid the favour by persuading Ansar members to instead pledge allegiance to him and initiated a bloodthirsty campaign of beheadings and bombings. Ansar never forgave Zarqawi for his rush to power, refusing to submit completely to his command when his star rose in the coming years.

Fattahi had returned to Iran in the late 1990s, where he revived Tawhidi’s Islamic Movement of Iranian Sunnis. The movement was ready when Jund al-Islam, then Ansar al-Islam called for help to smuggle in fighters. In return, movement members received military training from jihadists both foreign and Kurdish who had convened in the emirate, three jihadist sources in Iran who did not want to be named told Rudaw. The Iranian Kurds trained in Byara were part of the al-Aqsa brigade, under the direction of a Palestinian commander, Abu Zakaria told Hooshmand in 2011.

The emirate was seen to pose so serious a threat that the Americans showered Byara with Tomahawk missiles a few days after its war on Iraq began, then redoubled with a ground and air offensive a few days later. Upon loss of the emirate, remnant Ansar al-Islam fighters gathered at the Iraq-Iran border, where the IRGC turned a blind eye to the nighttime smuggle of a large number of the jihadists to the city of Mariwan in pick-up trucks.

Iranian Kurds who aided Ansar al-Islam refuge in Iran “obtained approval from the Iranian side, on the condition that the transportation [of Ansar fighters] was done quietly and secretly, and the Mujaheds be housed on the outskirts of cities and in remote neighbourhoods,” Abu Zakaria recalled.

If Ansar fighters were seen in groups, in cities, they would be arrested and deported back to Iraq, Iranian Kurdish supporters were warned. The IRGC ordered for the treatment of wounded fighters to be done in secret.

Some Ansar members brought their families with them; some were interned by authorities for two brief weeks, then released. Ansar al-Islam jihadists had a tacit agreement with the IRGC not to attack Iranian forces, to which they by and large adhered to.

Some jihadists returned to Iraq a few months later, re-organising themselves under a new organization called Ansar al-Sunna, and carried out terrorist activities against Kurdish, Iraqi and US-led coalition forces.

The accounts given by Abu Zakaria to Hooshmand were confirmed to Rudaw English by two other well-connected jihadist sources in Iran.

‘Golden age’ of Salafism

Those who remained in Iranian Kurdistan were able to grow ever more familiar with the idea of jihad. Salafist centers popped up in towns and villages across the Kurdish areas, propped up by preachers who travelled cross-country from Baluchestan.

Researcher Hooshmand spent over two years in prison for his political activism with Kurdish opposition groups from 2010. While serving his sentence at the city of Sanandaj’s Central Prison, he interviewed the jihadists who made up his fellow inmates. Interviews were conducted over 11 months, answers to probing questions crammed into the pages of 11 small notebooks, and smuggled out of the prison with a bribe to a guard for their destined publication, Hooshmand told Rudaw English from exile in Germany.

His research on jihadism long predated his time in prison. From 2004 onwards, he observed first-hand how jihadist ideology metastasised in Iranian Kurdistan, in what one Iranian jihadist told him was a “golden age” of Salafism. It lasted until 2009, when jihadis backed by the Iranian intelligence community betrayed them.

Amid jihadism’s ascent was Fattahi, who emerged at a mosque in Pishtap, a deprived neighbourhood in Mahabad, and found fertile ground to spew extremist ideologies and gain a huge following. The similarly deprived Mirawa neighbourhood of Bukan, West Azerbaijan province, where Fattahi had connections, was also a hotspot for radical preachers.

Fattahi and other orators railed against musicians and Sufis who visited the graves of saints. Their ardent followers took more than heed, destroying Sufi shrines, attacking those who drank alcohol and took drugs, and throwing acid in the faces of women who dared to wear make-up.

Kurdish Iran was being swept up by a tide of fanaticism, and Fattahi’s extreme approach was condemned by some Islamic scholars in the country. “Fattahi was argumentative and got into heated exchanges over interpretation of religious texts, even with the seminary scholars,” one source who knew Fattahi during his time in Mahabad told Rudaw English via an intermediary because of security risks. “He is very full of himself.”

The preachers also successfully encouraged their impressionable young congregations to pursue the path of jihad abroad. By the summer of 2004, when the first infamous battle for western Iraq’s Fallujah occurred, a highly developed network of jihadists with safe houses across Kurdish areas had taken form. The network would prepare young men to go to Iraq and fight the Americans – a phenomenon the Iranians saw no harm in turning a blind eye to.

That summer, one nationalist cleric in Bukan was tasked by a panicked friend with finding a young man who had gone missing.

"He asked me to help him track down his son who had been mingling with the Salafist group," Mala Hassan Waje told Rudaw English in May.

Waje called upon the services of a Salafist friend who had been briefly detained by the IRGC for his role in the Byara emirate, but was let go and allowed to “continue to propagate his Salafist message."

For the next two weeks, Mala Hassan and the father of the young man, accompanied by the Salafist friend, travelled north, to Mahabad, then Urmia, visiting a number of jihadist safe houses in the hope of finding the boy.

“We finally found him after making threats to the Salafist clerics. He was just about to be sent to Iraq,” he recalled. Waje believes dozens of other young men were not as lucky, succumbing to their foreign battlefield fate.

While Zarqawi gained notoriety in Iraq for presiding over an untold level of savagery – even by al-Qaeda standards – new, progressively more violent groups emerged in Iranian Kurdistan; first Kataib Qaeda in Kurdistan, then Jihad and Tawhid. The latter followed in Zarqawi’s footsteps, launching a terror campaign across cities in western Iran from 2009 until 2014. Most of the group’s leadership was detained and executed in a crackdown ordered by Khamenei, the avid translator of jihadist scholarship.

Where some Ansar followers saw benefit in the long haul, investing in education in medicine, physics and engineering alongside warfare, they viewed Fattahi and other groups who attacked Iranian forces as hotheaded, thoughtless thugs of jihad. But for what remained of Ansar al-Islam, adherence to Osama Bin Laden’s message that they should not attack Iran became more difficult as fellow group members were rounded up.

Fattahi was among the jihadists detained in the crackdown. He was held at Rajaei-Shahr prison near Tehran from 2010, alongside several dozen jihadists and other religious Sunni prisoners. A video leaked from the prison showed a long-bearded Fattahi speaking from behind a lectern in what appeared to be a Friday prayer sermon, launching stinging attacks on the Iranian authorities and corrupt Islamic world leaders, and encouraging his followers to disseminate the good fight.

“Being in prison is not the only way…there are other ways. which are hijra (migration) and jihad,” Fattahi preached.

Hijra to Syria

Many Iranian and Iraqi Kurds carried out jihad for the Islamic State when the group took over parts of Iraq and Syria in the summer of 2014. Ansar al-Islam remnants had regrouped around its longtime stronghold of Mosul, now the caliphate’s capital in Iraq – but the group’s stubborn refusal to pledge allegiance to Baghdadi and his caliph put them under pressure from the dominant ISIS, who detained and killed a number of Ansar al-Islam members. Some Iranian Kurdish fighters stayed with ISIS, but Ansar al-Islam’s close ties with the Iranian Kurds meant others rejoined Ansar in Idlib, to be received by what was then the Nusra Front.

Fattahi appears to have been released from Rajaei-Shahr in late 2014, but was warned he would be executed if arrested again. He was given a nudge to leave the country, two sources in Iran who knew Fattahi personally and declined to be named told Rudaw English.

Fattahi then made his way to Syria. It is not clear how he reached Idlib, but he was last seen in Iran in early 2015. The time Fattahi was released from prison marked the height of the influx of foreign fighters into Syria, who then joined Nusra Front and ISIS.

It appears that the Muhajerin of Iran group operated as part of Ansar al-Islam up until mid-2016. But as the Nusra Front changed its name to the Fath al-Sham Front and tried to consolidate power against both ISIS and President Assad loyalists, the Muhajerin joined the HTS fold. Ansar maintained its independence, but continued to work with the HTS. On July 2, 2016, the Muhajerin issued its first announcement pledging allegiance to Jawlani, and called on other jihadist groups to do the same.

Since the pledge, Iranian Kurds have found a warm reception in Syria, where they face compatriot adversaries in the form of IRGC members assisting Assad’s regime. HTS muftis have congratulated the Muhajerin for their steadfast bravery during the 2017 Hama offensive.

In an August 2018 visit to Idlib, HTS mufti Abu al-Fath al-Farghali reminded Sunni Iranian fighters of their transnational duty as jihadists.

“Your presence here is encouragement for other Iranian brothers to either come to this land and carry out jihad, or start jihad in their own land [Iran] for the Sunni people, because your land originally belongs to the Sunni people.”

Jolani said in a January 2020 interview with International Crisis Group that the HTS “has forsworn transnational jihadist ambitions, and is readying itself to focus on governing territory under its control.” The only HTS target today is Assad’s regime, Jolani claimed, and his organisation, considered a terrorist entity by the US and Russia, is independent of al-Qaeda’s chain of command, with a strictly Syrian, not transnational Islamist agenda. Two HTS-affiliated organisations – al-Qaeda offshoot Huras al-Din, and the Uighur Turkistan Islamic Party, active in Syria for seven years – have pledged not to use the country as a launchpad for attacks abroad, he said.

Though the HTS appears to have a “robust security apparatus” to keep tabs on its foreign affiliated organisation, “some foreign militants inside Idlib – for example, the Turkistanis – have actually said that they're fighting in part to accumulate combat experience that they can later deploy elsewhere,” independent analyst Sam Heller told Rudaw English.

With the seizure of Idlib by regime and Russian forces looming, Iranian Kurds and other foreign fighters may have to seek new destinations, carrying decades worth of crafted ideology and warfare with them.

The extent of jihadist fighter scatter from Idlib is primarily in Russian hands, Heller said. “It's Russia that decides whether to enable additional Syrian military advances in Idlib. The future of HTS's project in Idlib, then, depends largely on how far Russia is willing to push Turkey, and at what point Russia decides its own concerns about Idlib have been addressed” – though Heller said he is uncertain of a Russian push for a complete seizure of Idlib, “which would have grave humanitarian consequences and be really injurious to Turkish interests.”

The fighting experience accrued in Idlib could prove the perfect primer for jihadists on their way home, Heller said, perhaps catalysing Kurdish jihadism the way Afghanistan or the Byara Emirate proved to do for Kurdish jihadists past. In an unsettling indicator of what could come to pass, at least 17 people died in a jihadist suicide attack on Tehran in June 2017. Four of the five-member team that carried out the massacre were from Hawraman.

“Even individual veteran returnees may be able to capacitate a much larger number of inexperienced locals and turn them into something more dangerous... if those militants return to their countries of origin, the worry is that they will catalyze local militancy by, for example, contributing special expertise and transnational relationships, or acting as a nucleus for a local cell," Heller added.

Salafist jihadist ideology has spread to every corner of the Kurdish region in Iran, with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of young men like Zakaria and Faruq ready to take jihad up, the experts Rudaw English have spoken to concur. While dozens of Salafists remain behind bars at Rajaei-Shahr, supreme leader Ali Khamenei’s translation of yet another Sayyid Qutb book was released in 2019.

The threat of a Damascus-Moscow advance looming, the Muhajerin say now that their battle for Syria is but a stopping point in a war for the ages.

“Maybe we won’t see the fruit of what we are fighting for here,” a fighter says in a video published by the group this week, “but without a doubt, our children and descendants will obtain it.”

Editing by Shahla Omar

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment