The graves of Farhad Khusrawi, 17, and Azad Khusrawi, 21 in Nei village, Mariwan province of Iran. Photo: Jabar Dastbaz

SANANDAJ, Iran – At a mosque in Sailo, a neighborhood in the Iranian Kurdish city of Saqqez, a family holds a funeral. They mourn Kayhan, a 24-year-old kolbar shot by Iranian border guards while trekking through rugged frontier mountains to bring goods to Iran and make a living for his impoverished family.

Kayhan was shot and critically wounded in the Sarshiw area of Saqqez near the Kurdistan Region-Iran border, on September 14. His family did what they could to save his life, taking him to hospitals across Iran for treatment, but he passed away at Tehran’s Imam Khomeini Hospital on December 21.

Guests file into a funeral hall to pay their condolences. Tears run from the bloodshot eyes of Kamaran, Kayhan’s older brother, as he recalled the early pragmatism his brother showed to provide for his family.

"Kayhan dropped out of school when he was in the fifth grade because our family was poor. He was a smart and committed son, ready to do any job necessary just to make a living for us, so he eventually embarked on becoming a kolbar," Kamaran told Rudaw English as he sits in the corner of the room.

Kolbars are semi-legal porters who transport goods across the Kurdistan Region-Iran border, on backs horse or human. Some also smuggle banned goods like alcohol across the border.

It is a risky profession. They cross dangerous mountain passes rigged with legacy mines from the Iran-Iraq war. They also risk coming under fire from Iranian security forces. But economic hardships that compel young people to take on the job of kolbar have been compounded by US sanctions that have constricted the Iranian economy. Kolbars on the mountainside have said life has been made more difficult since US President Donald Trump's administration withdrew from the nuclear deal and re-imposed sanctions last year.

Kamaran, ten years older than Kayhan, recounts the events leading up to his young brother’s death.

"Seven months before he was wounded, he was forced to become a kolbar as the other jobs he was doing dried up," he said.

"On the night [of September 14] he left home for the Sarshiw border. Five hours later, one of his friends called us. My mother responded. They informed her that Kayhan had been injured. My mother immediately told me and my other brother. The three of us went to the scene, where we saw Kayhan had been shot on his right side [above his kidney]. His friends had carried him down the mountain. So, we rushed him to Saqqez Hospital in an ambulance, where he stayed for six days," he recounted.

Kayhan’s injuries deteriorated day after day. To pay for treatment to save his life, the family decided to sell all their possessions.

"We took Kayhan from Saqqez to Kawsar Hospital in Sanandaj, but his health kept deteriorating. So we eventually decided to take him to Tehran... We finally managed to have Kayhan taken in at Khomeini Hospital in Tehran," he said.

His family started borrowing money from relatives and friends to cover the massive cost of Kayhan's treatment. Then, they sold their family home.

The family had already spent 13 million tomans ($3,900) in Saqqez and another 66 million in Sanandaj before they arrived in Tehran.

"Kayhan became very thin, his weight fell to just 20 kilograms," he said while sobbing for the loss of his brother. "On the night of December 21, he fell unconscious for the third time. I hoped he would regain consciousness with the help of the physicians. But the doctors gave us the shattering news that he died."

Following Kayhan’s death, his family has taken on a lawyer to file a lawsuit against Iranian security forces, who dismiss claims of responsibility.

"But the border forces keep denying they opened fire on the kolbars that night, while his friends are eyewitnesses to Kayhan being shot and wounded by border forces,” Kamaran said.

His family also hold complaints against the hospitals for mistreatment of hospitalized kolbars.

"When hospitals know that the injured is a kolbar, they do not attend to him very well, believing he is a smuggler," he said. "My brother and thousands like him do this risky job to make a living, to afford a piece of bread, because of a lack of jobs in Kurdistan," he said through tears. "Poverty has forced them to open their chests up to border force bullets.”

Two kolbar brothers found frozen to death

Kayhan’s death is far from an isolated incident. The Paris-based Kurdistan Human Rights Network has recorded 245 incidents involving the death or injury of kolbars in 2019.

Iranian border guards and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) killed 56 kolbars and wounded 153 more according to the network. Another 23 kolbars froze to death in the mountains, drowned in rivers, or fell from cliffs. Thirteen were wounded by causes other than shootings.

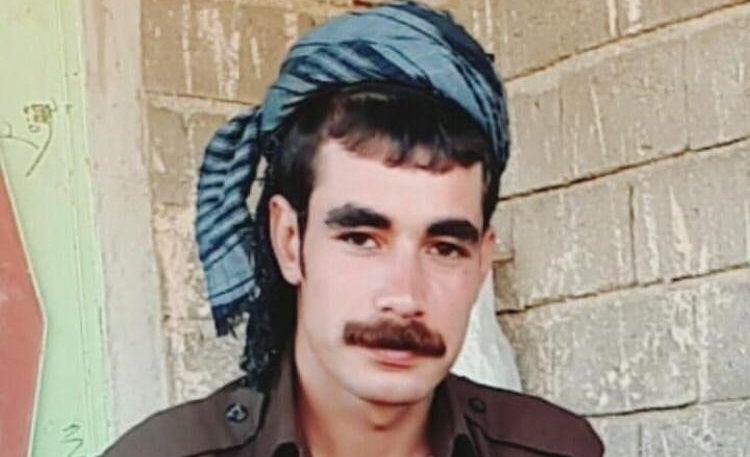

Four days before Kayhan died in Tehran, another two kolbars, Farhad Khusrawi, 17, and Azad Khusrawi, 21, went to work on Hawraman's snow-covered Tete mountain.

The brothers got lost in a blizzard and froze to death. Azad's body was found the next day; Farhad was found another two days later.

The death of the two brothers has shaken the conscience of people across Iranian Kurdistan and the country as a whole. Rudaw English spoke to their mourning relatives.

"They set off for work at 11 pm that night. I received a call at 7 am the next day, informing me that my sons were not doing well. One of my sons, Bahzad, and my brother Burhan went to find them. When they arrived, they found Azad had frozen to death and Farhad was missing,” their father Usman Khusrawi, 55, recalled.

“Many volunteers trekked to Tete mountain to search for Farhad. Unfortunately, after three days of continued search, they found Farhad dead too, right next to an orchard house. It looked as though Farhad had smashed the window of the house, but couldn’t climb in, eventually freezing to death."

Khusrawi said they pleaded for assistance from the border and security forces to locate his son and save his life on multiple occasions, "but they did not help us."

Amina Ahmed, their uncle’s wife, echoes a feeling that the authorities were willfully negligent of the young kolbars’ fate.

"This authority does not want the happiness of Kurds. According to what the physicians told us, Farhad had been alive just 24 hours before we discovered him. If the government was ready to provide a device to track them via their phones, our sons would not have died this way,” she said.

Distraught mother Rahima Pana grieves two sons simultaneously. "Azad's favorite hobby was to raise doves and other kinds of birds,” she recalled, while “Farhad was always complaining about our miserable conditions."

Burhan Khusrawi, their uncle, reminds us that the deaths of young Kurds who feel they have no option but to take on the profession are not exceptional.

"[It is] not just my nephews - many other people have become and will ruthlessly be made victims of such difficult journeys to make a living. In our village alone, tens of people have been killed by border force gunfire.”

Translation by Zhelwan Z. Wali

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment