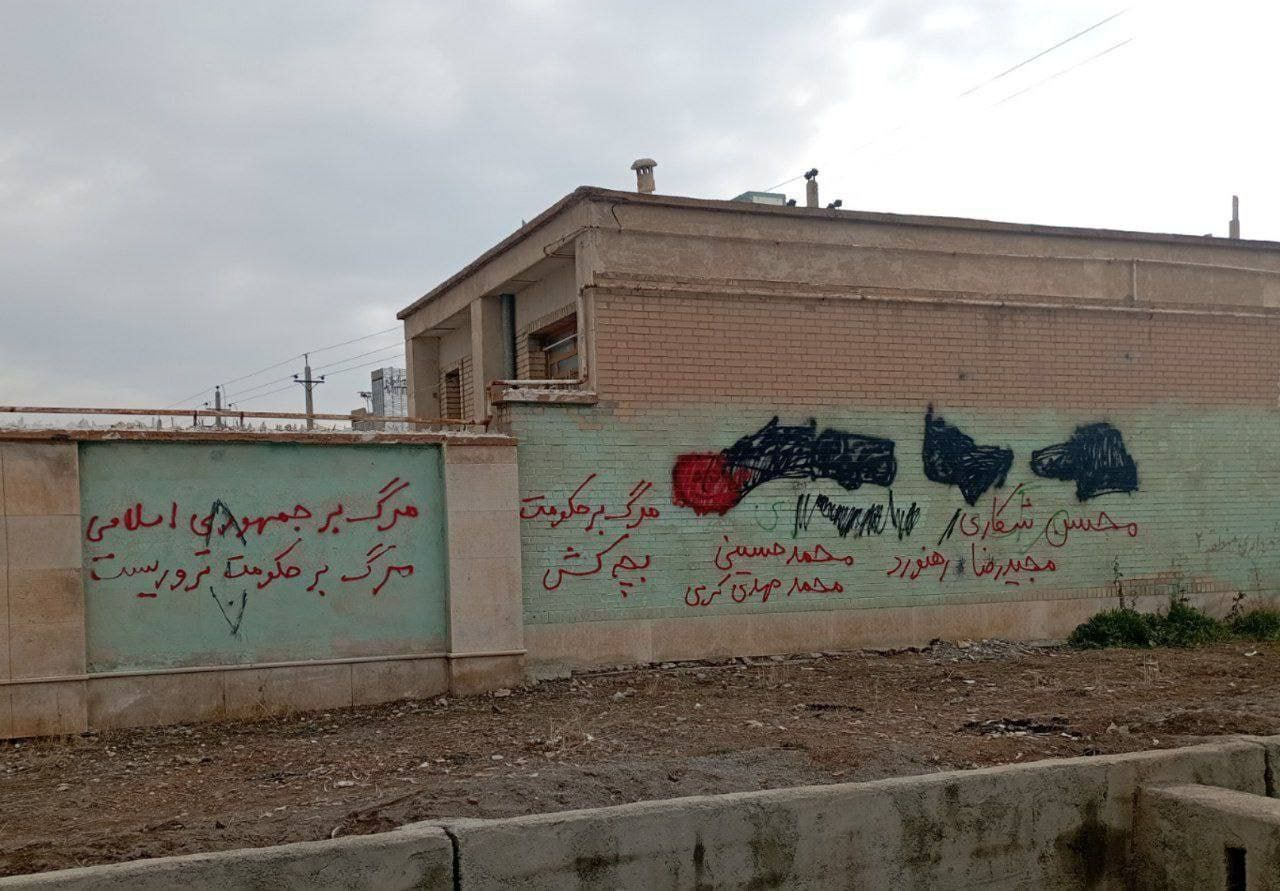

Hemin Jaleh (top) was severely beaten by Iranian security forces after participating in protests in the Kurdish city of Kermanshah in western Iran in November, 2022. Photo: submitted; Protests in Kermanshah on October 26, 2022. Photo: Hengaw Organization for Human Rights; Graphic: Aland Qaradaxi/Rudaw

As the sun set on a chilly autumn evening, hundreds of young men like Hemin Jaleh came out to show their displeasure with the Islamic Republic as they had done for almost two months across Iran. The intensity of the protests in Kurdish areas, including Kermanshah city, was unique. Dozens had died and many more were wounded. Hemin felt elated that he was taking part in a revolution against a corrupt regime that had taken his people hostage for over four decades.

But the regime had also deployed thousands of uniformed troops across the city to confront the protesters. Many more officers were in plain clothes and lurking in the shadows. In the blink of an eye, Hemin found himself bundled into the back of a car and taken to the office of one of the country’s intelligence branches, stripped of the thing he was chanting for - freedom.

Scores of people gathered in Kermanshah’s Nawbahar neighborhood demonstrating against the Islamic Republic’s theocratic rule when three cars filled with armed regime affiliates arrived and dozens of loyalist volunteer Basij forces swarmed the streets. Protesters, by and large peaceful, had become accustomed to the regime’s violent crackdown, but this time, it was different.

The same force that attacked the protest is accused of the murder of hundreds and arrest of thousands since the protests started. In their latest report on Wednesday, the US-based Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) said that at least 529 protesters, including 71 children, have been killed and over 19,700 have been arrested since the protests began.

Hemin was not shot dead that night like so many of his peers across the country. However, he spent ten days in a torture chamber. To stop the torture, Hemin said that he was prepared to admit to anything the interrogators wanted to accuse him of, true or not.

Hemin has had to go into hiding. Rudaw English spoke to him at an undisclosed location on February 2, where he told the nightmare he had lived during 16 days in the custody of the regime.

“When we started the protest, we chanted a few slogans,” Hemin recalled. Then the IRGC paramilitary forces arrived, “immediately - it was not like that before,” he said, comparing the quick arrival of the forces to the magical appearance of a djinn, sudden and without anyone realizing until it had happened.

Hemin was grabbed by three armed men and struck with two baton hits to the head. “I resisted a lot, in hopes of being helped, but there were so many, no one dared to get close,” he said.

He was brutally beaten by the armed men, until they took his broken down body and put him into the back of a car. What he saw next does not fall short of a horror movie.

Resonance

The nationwide protests against which the Iranian regime has unleashed horrific violence were sparked by the death of young Kurdish woman Zhina (Mahsa) Amini while in the custody of the morality police last September. The anti-regime protests were led by women, demanding greater freedoms and basic rights.

Zhina, whose Kurdish name was banned from being registered on her identification card and birth certificate, officially had to go by Mahsa Amini, the Persian name imposed on her by the regime. Kurds have been systematically oppressed under the Islamic Republic rule, including being banned from giving their children Kurdish names. Instead, they are often forced to pick a name that is either Islamic or Persian.

Despite knowing that he risked arrest or even death if he protested, Zhina’s story resonated with Hemin. Like her, he had a name enforced on him at birth. While his family and friends call him Hemin, to the regime he is Jalal Jaleh, a name he despises as a symbol of the oppression of his people. He joined the protest hoping that his voice would make a difference, in chorus with hundreds of others in Kermanshah where the regime has a strong military presence.

“When we are born in Iran, we are born with two crimes, one having a Kurdish name, and the other the fact that we are Sunni,” he said.

The Shiite regime in Tehran claims to be the true custodian of Islam and suppressing ethnic and religious minority groups such as Kurds, Sunnis, and Baluchis has been a common practice in its 44-year history.

In January, the regime began targeting Sunni clerics who had both directly and indirectly expressed support for the protest movement. Authorities detained two outspoken Kurdish clerics in late January, which raised the number of Sunni clerics in detention to at least ten. The pressure on the Sunni religious establishment is not limited to the Kurdish and Baluchi populations. Prominent figures in the Turkman areas in the north of the country have also come under increasing pressure from the authorities.

Hemin was no cleric, but he was both a Kurd and a Sunni. Growing up in the Shiite majority Kermanshah, he began encountering racism as a young child when he was mocked at school. These experiences stoked his anger against the state’s systematic racism. For him, and many others in Iran, the final goal is one thing, the fall of the Islamic regime.

“I have hope, because they have to go,” Hemin said.

Nightmare in custody

After he was picked up off the street, Hemin was interrogated and tortured for ten days in an office of one of Iran’s intelligence services.

“When they first took me to the station, the man [interrogator] did not say anything, they just hit me,” he said, showing a picture of injuries to his body.

When he wasn’t being interrogated, he was put in solitary confinement. The room was small. It had no windows and a light that never went off. “I lost track of time and could meet no one I knew,” he said.

His interrogations were accompanied by beatings. “Two people kept hitting me at first,” Hemin recalled.

At one point, he was brought to a table where an intelligence officer handed him a paper listing the accusations against him to read and sign. Unable to see without his glasses, Hemin asked the officer to read the paper for him.

“He would read it one at a time, and every time I said no, one would hit me in the head, kick me in the stomach, or hit my hands with a baton,” he said.

Among the accusations against Hemin were leading protests, damaging public property, and conspiring against the Islamic Republic.

At the time, Hemin’s family had searched for a lawyer, but, he said, no one dared take the case.

Under psychological and physical torture, Hemin felt he had no option but to sign the accusations against him.

“The officer then came up to me, put a hand on my shoulder, and said ‘now you are a good guy’.” he said.

With multiple injuries to his head and body, the intelligence office had Hemin seen by a man they claimed was a doctor. “The doctor came and said, here if you have pain, take this pill,” Hemin recalled. “But I did not take the pill because I had no idea what was in it.”

Hemin was transferred to a prison where the torture stopped, but he had to wait six days before being released on bail. His family put up their house and his father’s retirement pension as bail, but Hemin still had to go to court and received a summons on January 23, 2023.

Remembering the thousands who had been arrested under the regime’s rule during the four months of protests and sentenced to months and years in prison or to death; Hemin feared he would face a similar fate if he appeared in front of a judge.

The Iranian regime has long been the target of heavy criticism from the international community and rights groups for human rights violations and abuses in prisons, and use of torture and the death penalty in the country’s penal system. The full force of this penal system was being used against the protesters. Hemin knew that a death sentence was always a possibility, especially if he was found guilty of “enmity against God.”

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on February 5 approved pardoning and commuting the sentences of “tens of thousands” of prisoners, but the amnesty is conditional. It will not include those accused of or charged with committing “espionage” for foreign powers or having direct contact with foreign intelligence services, intentional murder or injury, and destruction and arson of government facilities. Protesters detained during the most recent demonstrations are also not included in the amnesty because, according to Khamenei, they have not shown remorse for their actions.

Instead of appearing in court, Hemin made the difficult choice to go into hiding. That decision means he had to leave his elderly mother and father behind.

Hemin’s father had for years experienced the brutality of the regime, watching relatives being shot to death, and friends arrested, never to be seen again. But seeing the news of the execution of two protesters in January was too much for him to bear. Mohammed Mahdi Karami and Seyyed Mohammed Hosseini had been accused by the state of attacking a Basij member, throwing stones at him, stabbing him, dragging him onto a highway in Karaj, west of the capital Tehran, and killing him. Their trial and execution was widely condemned.

When Hemin’s father heard the news that the two protesters were hanged, he suffered a stroke, which cost him sight in one of his eyes.

With tears in his own eyes, knowing that he may never be able to see his parents again and help them, Hemin is still proud that he took part in the protests.

“Protesting is a duty, I do not regret attending,” he said.

Hemin lives to tell his story, but the fates of thousands remain unknown inside Iran’s prisons and thousands more live with the fear of being persecuted for demanding the one right that everyone is supposed to be born with, freedom.

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment