From left: Zrar Sulaimani Bag, Halima Rahman and the flag of the Republic of Kurdistan. Graphic: Rudaw

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region - In the summer of 1946, a fearless Kurdish Peshmerga from what is now the Kurdistan Region visited a girls’ school in the newly-established Republic of Kurdistan (Mahabad) in northwestern Iran. The young man had gone to the young Kurdish autonomous region with the hope of defending it from the Iranian army. Little did he know that one early morning he would fall in love with the principal of the school and that maintaining their romantic relationship would become as hard as defending the republic.

Kurdish leader Qazi Muhammad founded the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI) in August 1945 and established the Republic of Kurdistan on January 22 of the next year. Thousands of Peshmerga fighters, who were fighting the Iraqi government in the north arrived in the Kurdish republic in Iran to defend it. One of these valiant fighters was the 19-year-old Zrar who had proven his bravery to his colleagues by deserting the Iraqi army twice and leaving with weapons to the Kurdish republic.

The Peshmerga fighters, led by Mulla Mustafa Barzani, arrived in the Republic of Kurdistan in April 1946. They were warmly welcomed by the Kurdish army, also called Peshmerga. They sought shelter in Naqadeh city where Zrar met a teacher and principal of a local school. She was to soon invade his thoughts.

Love at first sight

Zrar and other Peshmerga fighters were invited to a ceremony at a girls’ school in Naqadeh in the summer of 1946. The event began at 9am.

“In the beginning, the principal of the school delivered a short speech, welcoming the attendants. She announced the agenda of the party and highlighted the needs of the school. Then she gave a short speech. ‘All the shortcomings should be addressed by the beginning of the new academic year with the help of everyone,’ she said enthusiastically,” writes Zrar in his memoir, published in the early 2000s.

“After the party ended, I returned home and thought about the female teacher,” adds the Peshmerga fighter who had not expected to fall in love when he made the difficult decision to take up arms for the young Kurdish republic.

Later that day, Zrar saw Ali Rawkawan, a postman.

“Ali, I want you to do me a favour but you have to keep it between us,” Zrar told him quietly, then asking who the father of the woman was. ‘She is the daughter of Wasta Rahman the tailor who is originally from Sablagh. They have been living in Naqadeh for a long time and are good people,’ replied the postman.

Zrar inquired if she was married and the answer that followed resonated well with him. “She is neither engaged nor married. She is young and has recently graduated,” said Ali.

But the rest of the response troubled him a little. “Many people have asked for her hand but she has refused to get married.”

The postman stared at Zrar for a while and said, “It seems that you have a crush on her.”

Without waiting for a confirmation from Zrar about his feelings, Ali excitedly asked him to write a letter to the teacher, saying he would also deliver the reply. Zrar agreed without any hesitation, asking him to pick up the letter in the evening.

“I took a pencil and began writing a fancy letter. In the evening, Ali came and took the letter. I waited for a reply for two days and received a well-written letter which read, ‘Dear Z, I have received your letter. I understood the content well. It seems from the letter that you have come all the way [from Iraq] to get married rather than serving the Republic of Kurdistan. Please do not get upset with my letter but it is early for you to get married,’ according to Zrar’s memoir.

“The response to the letter disappointed me. Whenever I thought of her, I tried to forget her and sometimes I would go to Hassan Lyan pond… to hunt seabirds just to avoid thinking about her,” says the Peshmerga fighter in his book.

A conditional ‘Yes’ followed

Kurds in Naqadeh used to picnic on Wednesdays, gathering to dance and revive Kurdish culture. In August 1946, Zrar attended these festivities although he did not know the people.

“Suddenly, I realized that the girl that I had sent a letter to held my hand and joined the dance. It was strange to me,” says Zrar.

The girl’s father then invited him and a friend to lunch. They initially refused as they had been invited by another person but after the father insisted, they accepted.

“They really respected us [at home]… I could feel a change in the girl’s position. We had a good day,” recounts the Peshmerga. “After this [invitation] and an exchange of letters, the girl agreed for her hand to be asked but on the condition that the marriage ceremony should be postponed. I agreed.”

The teacher’s conditional “Yes” put a unique smile on the face of the Peshmerga fighter but he also needed the approval from his father, who was also in the Republic of Kurdistan.

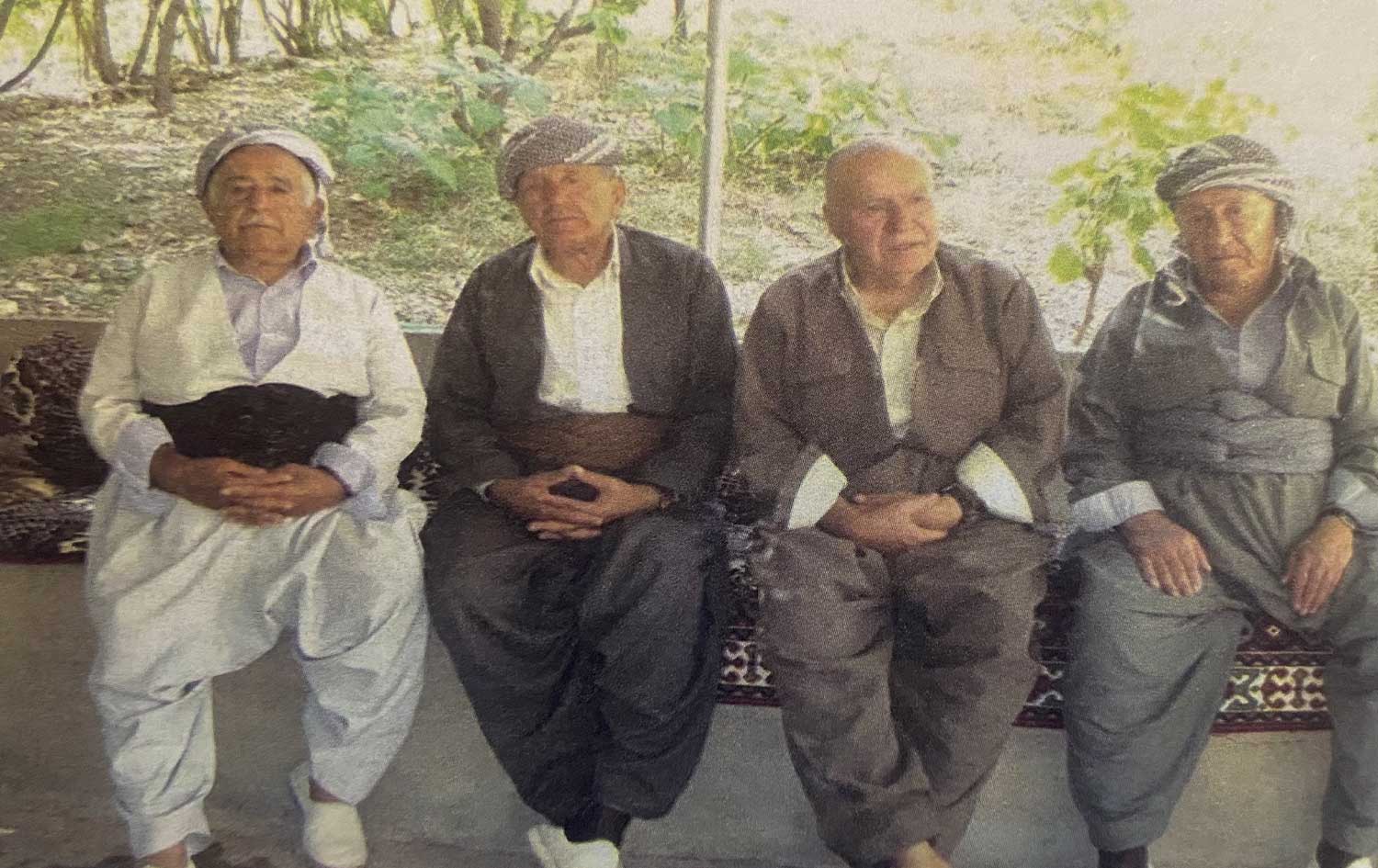

“Zrar asked his father, Sulaiman Bag, to ask for her hand but Sulaimani Bag did not approve because the situation in Mahabad was not really suitable for marriage. However, when Barzani learnt about this, he himself asked for her hand [on behalf of Zrar],” Krmanj Izzet, Zrar’s nephew, told Rudaw English in the scorching summer of 2022 in Kurdistan Region’s capital city of Erbil.

Krmanj has also penned the memoir of his father, Izzet, who had accompanied Zrar and their father to the Republic of Mahabad.

The couple officially got married in late August 1946.

Collapse of the Republic

The Republic of Kurdistan was founded after the Soviet Union seized control of parts of Iran in the early forties. The Kurdish enclave and its sister, the Azerbaijan People’s Government, relied on Soviet support against the will of the West.

In March 1946, the Soviets promised to leave Iran following pressure from Western countries. This helped the central government to reassert its control over areas it lost to Kurds and Azeris.

Kurdish authorities started talks with the Iranian royal dynasty after the central government launched attacks against both young republics. Despite months of negotiations, both sides failed to reach an agreement.

The Azeri republic collapsed in December 1946, causing chaos in Kurdish areas. The Republic of Mahabad army and Barzani’s fighters fiercely fought the kingdom’s army but it was not enough. The president of the Kurdish republic decided to stop fighting to prevent a massacre of Kurds, with Kurdish autonomy unofficially ending in mid-December after the capital city of Mahabad was retaken by Iranian forces, with some bordering areas remaining under Kurdish control. President Muhammad asked General Barzani and his fighters to escape as Iran retook more and more land. Therefore, the president surrendered to avoid bloodshed. He and some other top officials of his cabinet were then hanged on March 31, 1947.

Krmanj told Rudaw English that his uncle and the teacher stayed together until April 10, 1947 when Halima and Zrar’s brothers went to his home in Dargala village in Erbil province, while he accompanied Barzani and about 500 other Peshmerga fighters to the Soviet Union.

After months of walking and fighting the Iraqi and Iranian forces, Barzani and his fighters made it to the Soviet Union in late June.

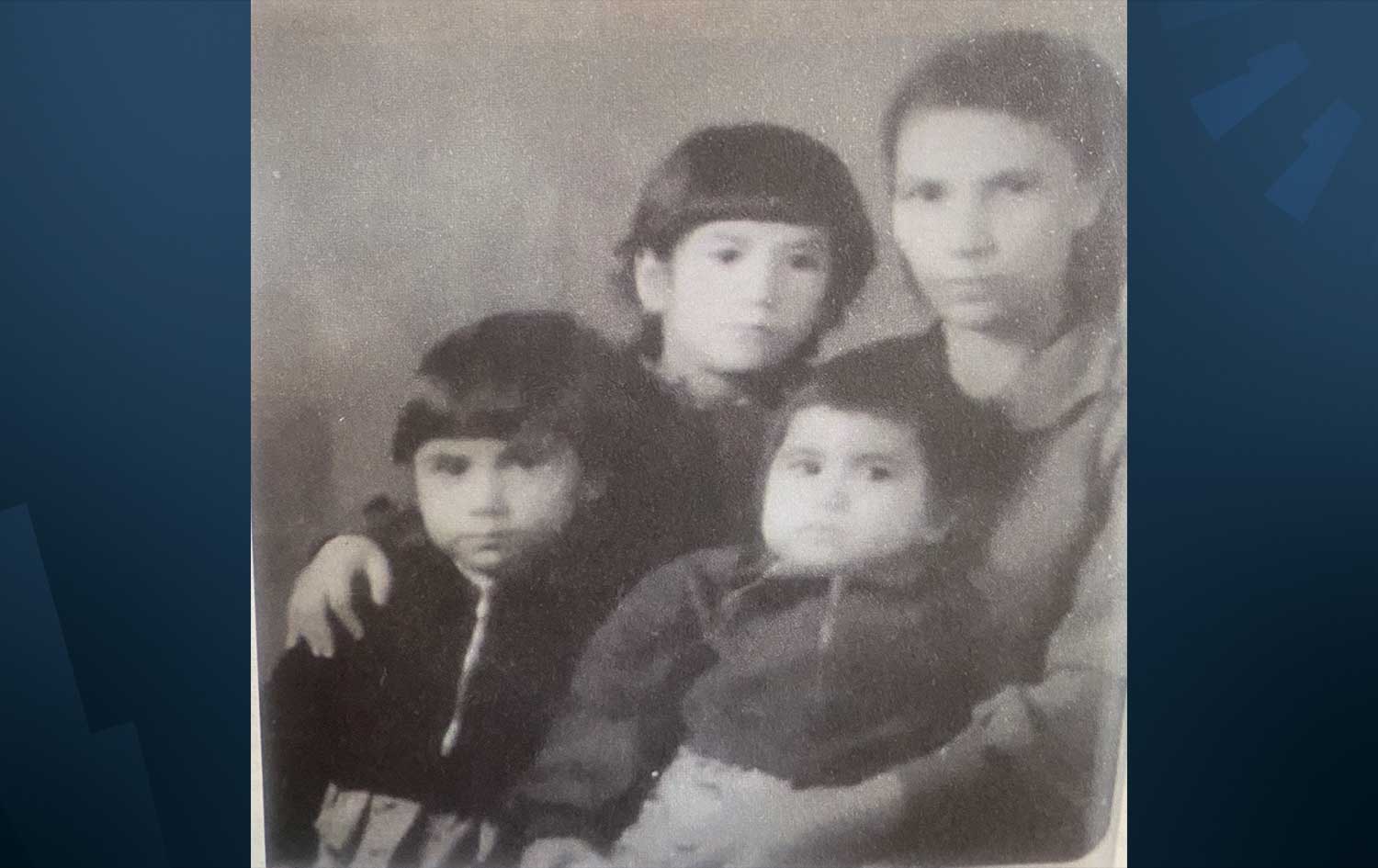

“She was pregnant and gave birth to a son, Sardar, who died four years later after suffering from an illness,” Krmanj said.

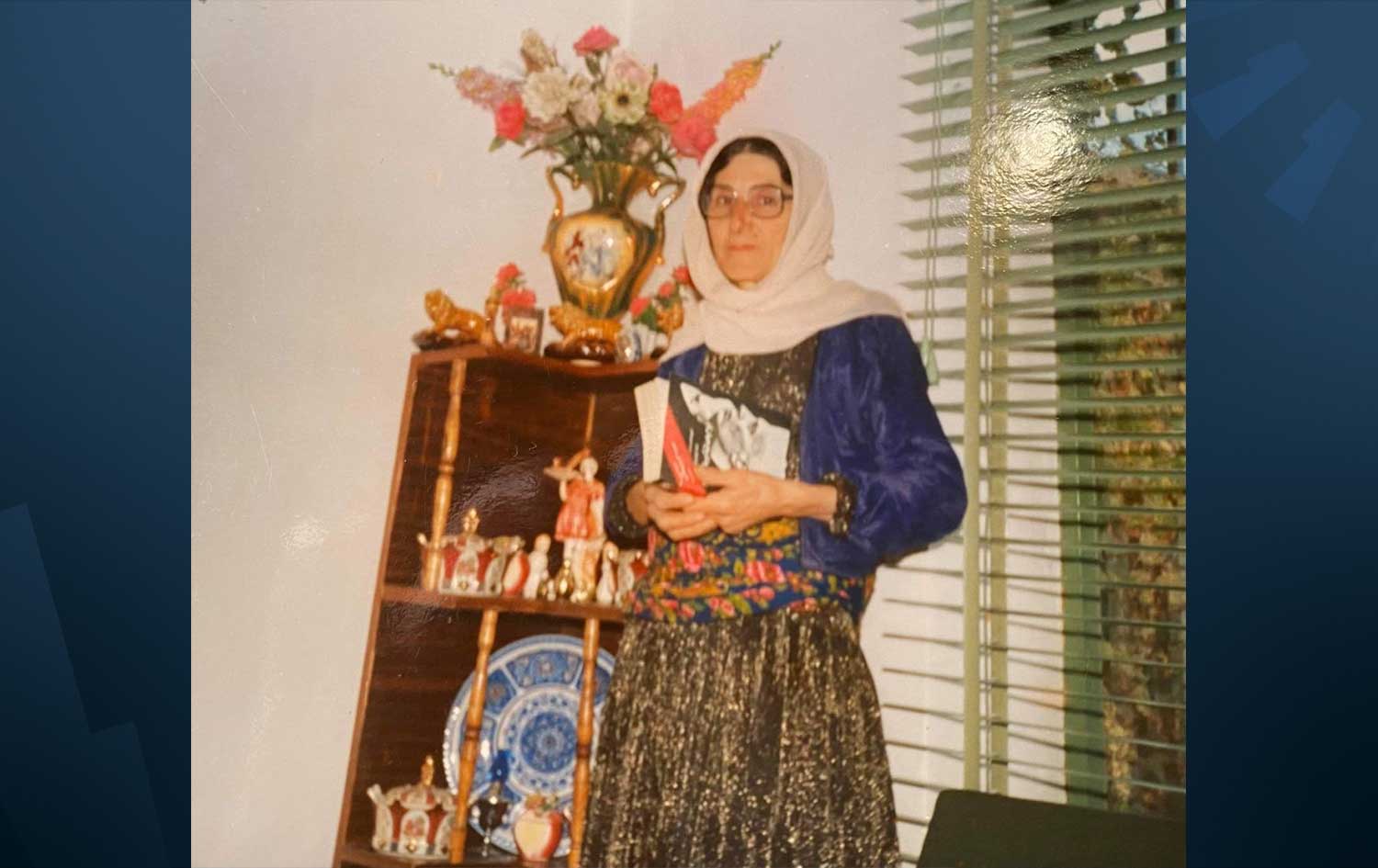

He also said that Dargala lacked basic services and did not have a school but Halima started teaching the Kurdish language to villagers, having a positive influence on women “because she was an educated and intelligent woman.”

A resident of the village, Qadir Mulla Ahmed, says in his memoir published in 2018 that Halima taught him the Kurdish language.

“She was a loyal teacher who taught a group of students in Dargala. I was one of the students who really benefited from her. She taught us Kurdish lessons and the [Kurdish] national anthem,” he recounts in his book. “She also taught us moral lessons and recounted very interesting stories.”

A sorrowful ending

Months after receiving no news from her husband, the teacher returned to Naqadeh with the hope of finding him. She was finally able to contact him and they exchanged letters for a while.

On July 14, 1958, Abd al-Karim Qasim, an Iraqi army commander, led a coup that ended decades of monarchy rule in Iraq, and he took charge of the new republic in Iraq. He issued an amnesty for Barzani and his fighters, who returned to Iraq in October, along with some of his men – and their new families.

While in the Soviet Union, Zrar had married Zahra Hassan, a Tatar, from whom he had three daughters. Tatars are a Turkic-speaking people who live in Tataristan as well as other places, especially Russia and Ukraine.

Zrar says in his memoir that he did not want to get married in the Soviet Union but it was not easy for a man to live alone there. Halima was not initially aware of this marriage.

Many of the Peshmerga fighters who accompanied General Barzani to the Soviet Union got married during their time there. A large number of these women accompanied their husbands back to what is now the Kurdistan Region in 1958.

RELATED: The Russian widows of first generation Peshmerga

When Zrar returned to Dargala, Halima was there as well. She was taken aback by the news that Zrar had taken a second wife but did not protest and offered reunion. Zahra refused this and told Zrar he had to choose between her and his first wife. Halima did not want to give up but her parents forced her to request a divorce and return to Naqadeh where she married another person, according to Krmanj.

She gave birth to a daughter, Mirya, and a son, Salah, in her second marriage. Both children are still alive.

Krmanj told Rudaw English that despite the divorce, they remained in good contact with Halima, as well as her new husband and children. When Zrar’s expanded family was displaced to Mahabad city in 1974 due to unrest at home, Halima would often visit them there. Zrar’s son from the Tatar woman fled to Iran but could not find a place to live. His father's ex-wife took him to Naqadeh and allowed him to stay at her house for a long time.

Halima and her family migrated to Canada and when she returned to Iran in 2005 she passed away just before her plane left Iran, according to Krmanj. Zrar died in the Kurdistan Region in May 2018.

Zrar and Halima’s love story began in the early months of a Kurdish mini-state which millions of Kurds are proud of. The short-lived republic is commemorated annually and the social contact between the teacher and the Peshmerga fighters created a permanent cord between their children and grandchildren.

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment