ERBIL, Kurdistan Region - The Kurdistan Region has given oil companies 18 months to stop flaring associated gas, a toxic byproduct of crude oil production that has been burned off at the Region’s oil fields since day one. The move would end the environmentally damaging practice, but it is unclear whether the Kurdistan Region will be able to make use of the gas given its underdeveloped industry and the amount of debt it already owes to the oil companies.

On July 13, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) Minister of Natural Resources Kamal Atroshi issued a decree giving oil production companies in the Kurdistan Region 18 months to put a complete end to flaring, as first reported by the Iraq Oil Report. Atroshi was sworn in as minister in January, taking over the key ministry that was managed for 13 years by his predecessor, Ashty Hawrami.

The KRG, however, is likely to face complications in obliging the companies to shift to a high cost process, even with the threat of taxes as punishment for those who do not comply. Eighteen months may not be enough of a heads up.

“For some companies it might be doable, but others might need an extension. There are going to be issues, because you are not in Texas or Saudi Arabia where the industry is very mature,” Shwan Zulal, political analyst and managing director of Carduchi Consulting, told Rudaw English.

“Some companies might even resist and say this is not part of our contract, we are not mobilized to do it, we will do it when we think we are in the right position,” he added.

There are 52 oil blocks in the Kurdistan Region, 16 of them are in production and 15 are in exploration phases. Over 30 international and local companies are working in the sector. Many of the contracts were signed with prepayment schemes, and the Kurdistan Region owes a large amount of money, that could be a factor in efforts to end flaring.

In late June, the Council of Ministers Secretary General Amanj Raheem told parliament that the KRG owes around $4.3 billion to oil companies. The government has also said it inherited $28 billion in debt from the previous administration.

Among the many companies that the KRG still owes money to is Genel Energy, which on Friday said Erbil served them notice it intends to terminate two contracts. In late July, the company said they were paid $30.4 million for oil sales during May, but are still owed $141 million.

According to Zulal, if the KRG can make payments on time, then a smooth transition to end flaring is possible.

“The financial viability really depends on if the KRG pays them. If they are paid on time and with no delays, it should be possible, especially with the current oil prices. There’s no issues because everyone else does so in many places, and flaring is not really the way forward in oil industry, especially with all the climate change,” he said.

“Generally what happens is if a company spends money in accommodating the flaring, they usually count it as cost. In the end the KRG is to pay for it,” he added. “If they are getting paid, there is no reason why they should not be able to stop it.”

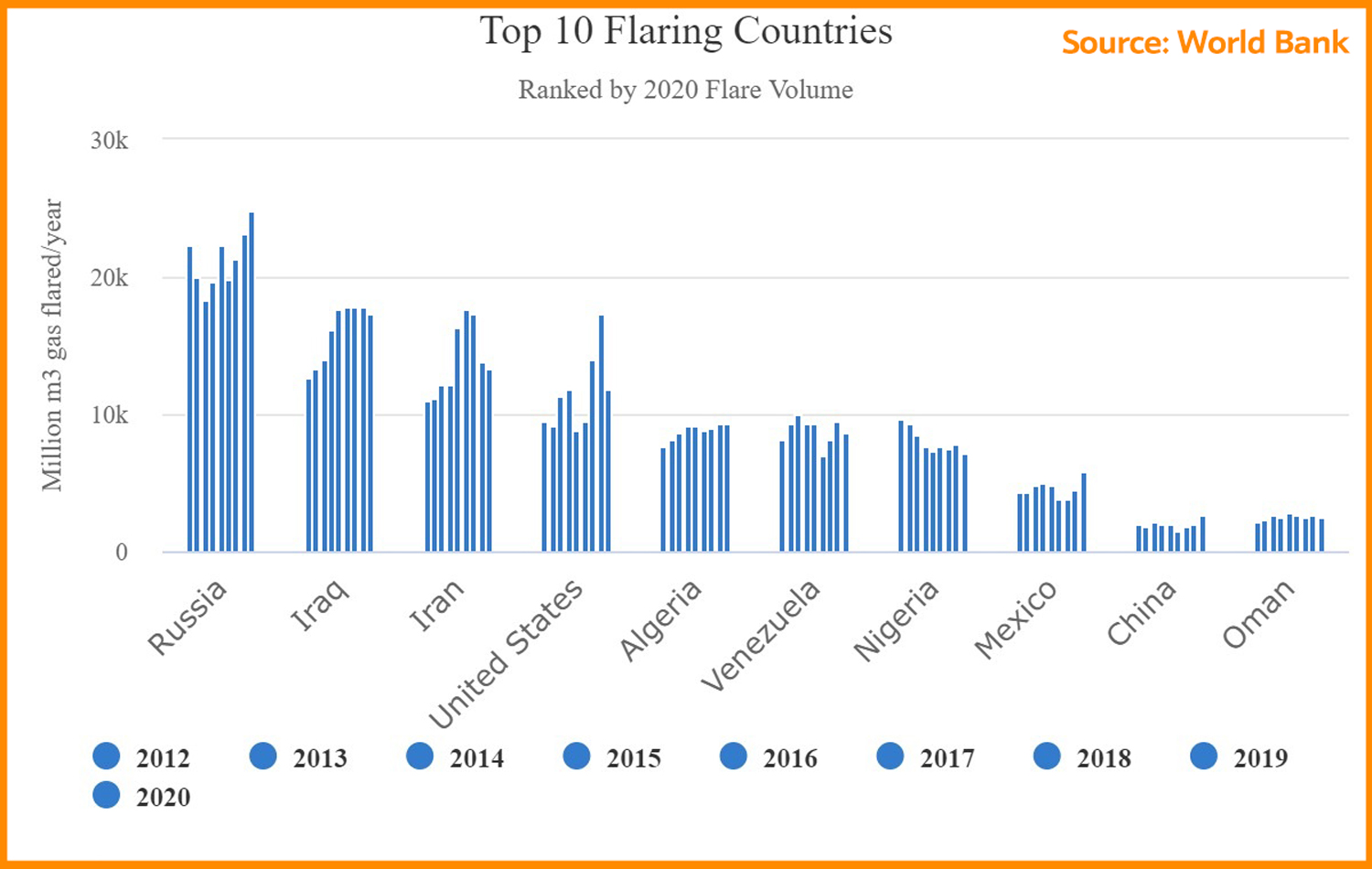

Iraq ranks second globally in flaring associated gas, behind Russia. According to the World Bank, in 2020 Iraq flared 17.37 billion cubic meters of gas and Russia burned off 24.88 billion.

Atroshi said the Kurdistan Region has been flaring more than 150 million cubic feet of associated gas every day for 15 years and that has to stop. Any company that fails to comply with the decree set by the ministry will have to pay a tax.

“They either abide by this or they go and burn it in their own homes, for which they will be imprisoned. A cubic centimeter of that gas being flared is illegal everywhere,” he said in an interview with Rudaw earlier this month.

Ceasing flaring requires a financial commitment and experts to do the job. According to Zulal, several factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, supply chain problems, and a lack of specialist gas engineering companies in Kurdistan who can do these projects might eventually require the government to extend the deadline for some companies.

Environment officials of the Kurdistan Region believe that if the associated gas is not flared, but is instead used, it could help the KRG pocket a lot of money, however neither the Iraqi government nor the KRG have the financial or technical capacity to do so.

“If this gas is not burned, it is able to produce electricity for around 3 million houses,” Abdulrahman Sadiq, head of the Kurdistan Region’s environment board told Rudaw English.

“The problem is that Iraq no longer has the facilities to make use of this gas, and Kurdistan Region does not have the expensive and new technology to make use of it and not waste it,” he explained. Increased oil production will also mean more associated gas, he added.

The KRG has proposed a solution, one that is not cheap per se, but in comparison to processing the highly toxic associated gas, is more cost-effective.

“We are not burning it. We cannot use it to make food because it is poisonous. So we decided that we would put it back underground, 4 to 5 thousand meters into the reservoirs. The usefulness of this is that you put it back into its place and it increases our oil production as it pressures the water under the oil, and reduces cost,” said Atroshi.

Re-injecting associated gas is a process done in many countries across the world. The associated gas is injected back deep into the ground where it increases water pressure in the reservoir, boosting the flow of oil.

“Capturing gas is not cheap, but it is not as expensive as drilling new wells. The cost in some cases can be recoverable. If it is injected that can help increase the flow of the field, so there are benefits for the companies as well,” Zulal said.

Enforcing the new rule, however, could be difficult. Flaring associated gas at oil fields across the Kurdistan Region has been the status quo for years.

“Companies go back to the contracts, and it is hard to speculate how they are going to be interpreted. I am sure there are parts about capturing gas, but it has not been enforced for over 15 years, and you cannot just all of a sudden enforce it now. You have to give companies time,” Zulal said, adding that the companies have gotten comfortable with the idea of flaring without any consequences.

In the face of the climate crisis, at least one oil company has already made the decision to stop flaring and slash its emissions. The Norwegian oil and gas operator DNO ASA in September said their $110 million Peshkabir Gas Capture and Injection Project at their Tawke license in Duhok was onstream and had re-injected one billion cubic feet of gas, proving the possibility of a transition.

“Gas injection and the associated carbon capture and storage is proven, practical and potentially profitable,” DNO’s Executive Chairman Bijan Mossavar-Rahmani said at the time. “Our project was completed on schedule and on budget notwithstanding the challenges of working in what is still a frontier oil and gas operating environment and the obstacles posed in the late stages by the Covid-19 pandemic.”

The company said they reduced gas flaring by 75 percent at Peshkabir and were aiming to reduce it even further, reducing annual CO2 emissions by more than 300,000 tonnes.

The United Nations released a key climate report earlier this month warning that the earth is close to irreversible tipping points in terms of climate change.

“The probability of low-likelihood, high impact outcomes increases with higher global warming levels,” the report said. “Abrupt responses and tipping points of the climate system, such as strongly increased Antarctic ice sheet melt and forest dieback, cannot be ruled out.”

In December, the UN called on Iraq to take “urgent climate action” as it is “one of the most climate vulnerable countries in the world.”

Compared to cities in southern Iraq, the Kurdistan Region has cooler, more bearable weather, but temperatures are rising. According to data from the Kurdistan Region’s statistics office, average temperatures have risen by 2.52 percent in 2020 in comparison to 2012.

Emissions from the oil industry are also a health hazard, especially in cities like Kirkuk.

“We live in an oil-rich city. The gasses that exist in the air of our city carry most of the heavy [pollutants], resulting in breathing problems and poisoning and asthma, as well as blood and lung cancers,” Pakiza Fuad, a microbiologist from Kirkuk told Rudaw.

The Kirkuk Oncology and Hematology Centre has registered 1,450 new patients in the past eight months. That’s six new patients every day and nearly half of them have cancer.

“Oil refineries pose a serious threat to cities' air pollution, which can lead to serious health problems, such as cancer. It has also caused psychological problems for the residents. In and outside of the city, there’s no green space for people to relax. Usually when they need a break, they go to Sulaimani or Erbil," said Nyaz Ahmed Amin, the director of the centre.

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment