SULAIMANI, Kurdistan Region — Surkew Zahid left his home in Sulaimani ready to jump the next hurdle of his high school education. “I have two exams. If I pass, I’ll come home celebrating,” Surkew told his mother, before stepping out into February cloud cover.

After finishing his exams, the 16-year-old headed to anti-government protests that were taking place in the city center’s Sera Square in 2011. Like so much of the youth in Sulaimani and the rest of the Kurdistan Region, he wanted passing his exams to mean something for his future.

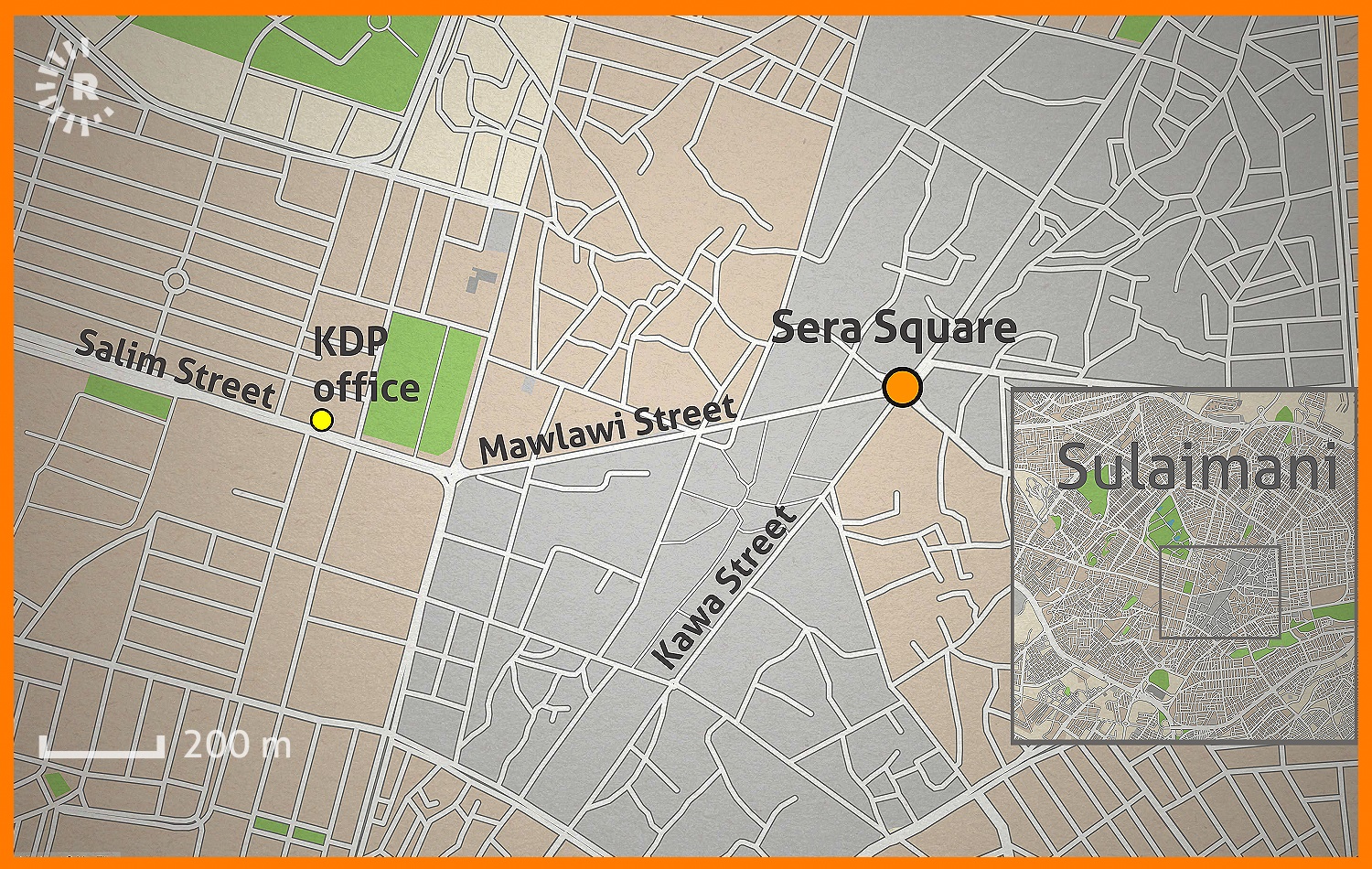

Surkew was shot by security forces on a road leading off of Sera Square. He was rushed to hospital, where he died from his wounds.

In the house Surkew called home, his father sits on an old iron bed moved to the living room to accommodate for his health issues, among them a limp that has worsened over time. On the wall he faces are pictures of Surkew and the other seven people killed in the protests of 2011, hung in order from first to last, a reminder too painful for even the medications he keeps under his pillow to mend.

Protests broke out in Sulaimani on February 17, 2011 as a wave of anti-government demonstrations engulfed neighboring countries, in what Western observers branded the Arab Spring. People in Sulaimani had grown tired of the two-party rule of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which they accused of corruption and repression. Organizers say that though the Arab Spring did serve as some inspiration to the protesters, their motives were local.

Protests stopped for a couple of days after a brutal crackdown on the 17th, before starting up again on February 20. Unbeknown to Surkew, his father Zahid Mahmood had also decided to attend the protest, limp and all.

“Surkew told me, ‘Dad, do not come to the protests. You’re limping, and if you fall over, people will run you over’,” Zahid said.

Going against the advice of his protective son, Zahid headed to Sera Square.

“I heard gunfire down Kawa Street, and in that moment, my heart felt tight and I knew something bad had happened,” he said.

“I rushed down the street with my limping leg, I had bought bread to take home, and I asked a few people coming up the street about what happened, and they told me that people had been injured… I got home, took one arm out of my jacket when I got the phone call, and that was it.”

On February 17, protesters gathered in Sulaimani’s Sera Square for a peaceful protest that they had received permission for from the governorate. They packed up once their officially-approved hour was up, but one small group called on people to follow them to Salim Street, which runs through the city’s center.

When the protesters passed the KDP’s office, they and the guards clashed, the sound of pistol and AK-47 fire soon filling the streets. Accounts of what happened vary, but officially, protesters threw stones at their office, and in return, the guards on the roof were shooting at the protesters.

That was when 17-year-old Rezhwan Ali became the first victim of the protests; his death would be the fuel for weeks of demonstrations.

“After the 17th, the death of Rezhwan and injury of many others, people were angry, though they could not protest because security forces had blocked all the main streets,” Zahid said.

Zahid said he knows who killed his son and who ordered the shooting and has filed several lawsuits against them, however his latest appeal case has not received a response from Erbil for the past two and a half years.

“The night Surkew died, I got a call from a PUK official, urging us to bury him the same night as I had said that I would hold a ceremony at Sera Square and then take him to be buried,” Zahid said.

Later that night, he received phone calls from two leading officials, one from the KDP and the other from the PUK, who told him that they wanted to attend the funeral. Zahid told them that they, like anyone else, could attend. There were only two conditions – that they were not to take photos or videos, and TV channels were not to be present. Neither official showed up to the funeral.

Outrage over the protest killings forced government officials to respond. Barham Salih, the Kurdistan Region's prime minister at the time, addressed the parliament, saying that there were "indeed shortcomings from the government's side, and that they should work toward giving the people their legitimate requests." He was subject to a vote of no confidence, but enough parliamentarians voted in his favor to keep him in the role.

KDP officials said the protests were suspicious, asking why their party’s office would be attacked in a city they do not govern. They said that the protests were influenced by external forces – a stance they have maintained in the face of successive waves of protest.

The events of February 17 and 20 led to daily protests that lasted two months in Sera Square, to a point that the space became known as Freedom Sera – a name that many of those who remember the events carry. Every day, hundreds, even thousands of people would gather, calling for reform and preaching against corruption. On the podium they crowded around was speaker Ismail Abdullah, with a voice so loud that his microphone was more accessory than necessity.

Ismail was chosen as protest spokesperson after a council by the name of “February 17 protesters council” was formed by the protesters on March 20.

He disputes the account of events the KDP gave at the time of February 17, saying that protesters threw stones at the office, and that was when the clashes started, however Ismail claimed otherwise, saying that “when we got onto Salim Street, we passed by the KDP office when one of the guards threw a stone at one of the protester’s head”.

“The situation escalated from there, and soon enough, all the guards ran to the roof shooting at protesters with their guns,” Ismail said.

Founded in 2009 by former members of the PUK, Change Movement (Gorran) was then the biggest opposition party in the Kurdistan Region and played a main role in the protests. Its members and even MPs were frequent attendees, it dedicated its TV channel, KNN, to covering the daily activities of the protesters. During Newroz celebrations on March 20, the party’s head, the late Nawshirwan Mustafa, paid a visit to Sera Square, to a rapturous welcome from thousands of protesters. The party went on to beat the PUK in the 2013 parliamentary elections, and Ismail has since become a member of Gorran himself.

But in the years since 2011, the party has transformed from an opposition party in vocal support of protests to a member of the government’s cabinet.

Critics say the party has abandoned its cause, but Ismail is firm in his belief that his party has done the right thing.

“Change can not always be achieved from outside, but rather from inside the government,” he said in a garden on Zargata Hill, where Gorran’s headquarters are located. “After all, the protests asked for reform.”

An abrupt end to the protests came on the evening of April 19. In the dark and quiet that followed another day of protest, security forces were deployed to the Square and the grand bazaar, where they burned down the podium and all the hung banners.

“The next day, a huge amount of security forces including the Peshmerga and the Asayish were deployed to the grand bazaar and all over the Square, forbidding anyone from returning to the Square and arresting all those who attempted to do so,” Ismail said.

Ten years have passed, but none of those who killed or assaulted the protesters have been held accountable. The eight people killed and more than a hundred injured have not received justice, according to Zahid and Ismail, which both say they won’t be giving up on any time soon.

With a similar resilience, the city of Sulaimani has not stopped its protests. The latest wave of demonstrations took place in December 2020, Sera Square once again their center. Teachers and other civil servants demanded that they be given their salaries, which had been going unpaid or delayed for most of the year, in what the KRG blamed on budget disputes between Erbil and Baghdad. Protests took place in numerous towns in the provinces of Halabja and Sulaimani. Eight civilians and two Peshmerga officers were killed, before the protests were hushed once more.

Though recurring waves of protest have resulted in very little in the way of change from the government, speaker Ismail believes their impact has been profound.

“People say that the protests failed, but I disagree," he said. "The protests were a starting point to show the government that people will no longer sit down and watch, but they will speak up in the face of injustice and corruption."

With reporting by Mohammed Othman