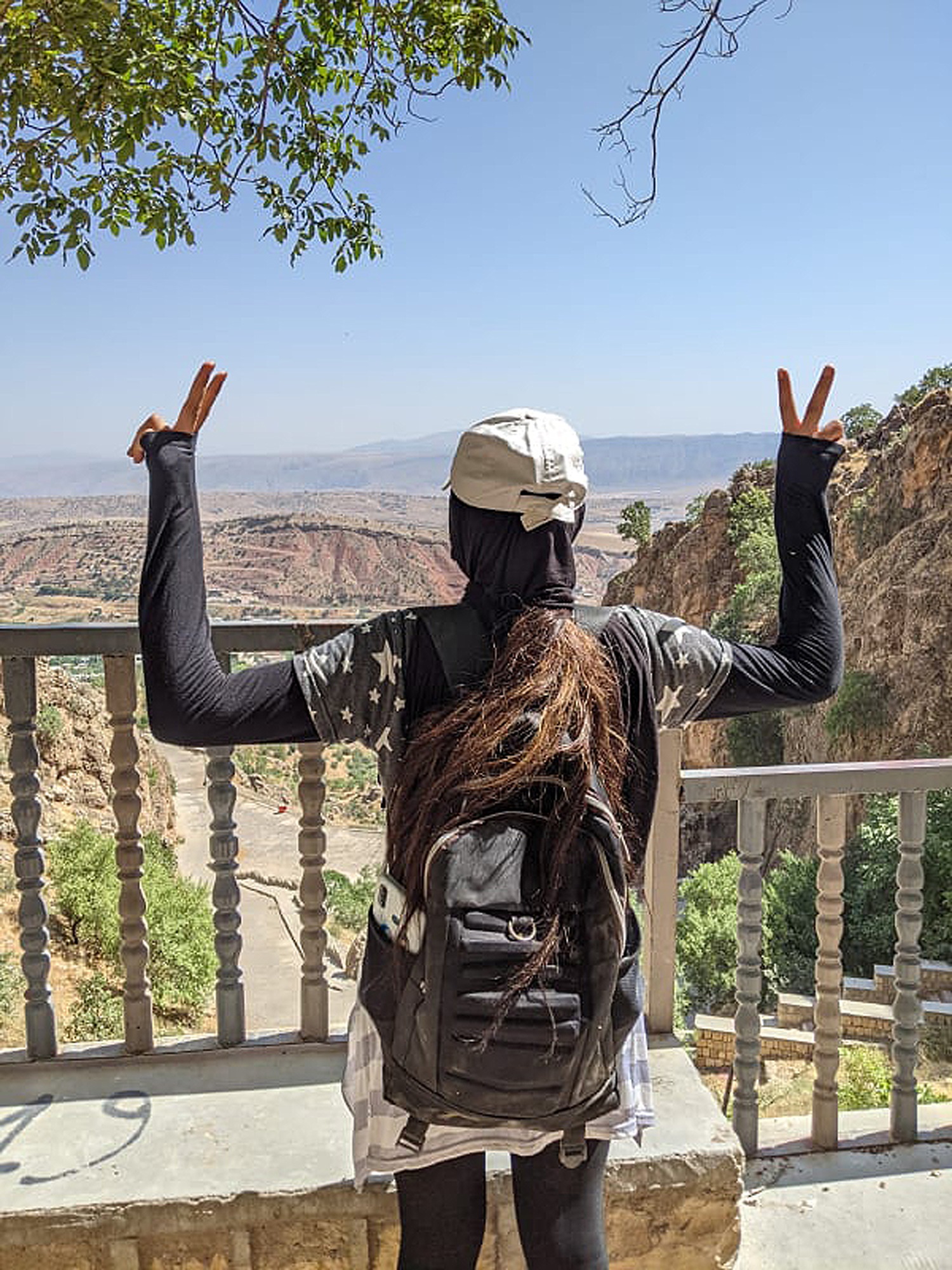

Abeer and her son Ali attend a training session of the Free to Run organization in Erbil on July 15, 2021. Photo: Layal Shakir/Rudaw

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — At the break of day the sun is already blisteringly hot, leaving even the birds gasping for air. A group of young women get out of two minibuses and slowly make their way to the running track in Erbil’s Sami Abdulrahman Park. Their murmured conversations in different languages and accents are carried on the hot, dry wind.

One of the women, Abeer*, carries her one-year-old baby boy, Ali, in her arms. Memories of the brutality she witnessed when the Islamic State group (ISIS) attacked her home in the city of Mosul are far from her mind as she gently lays a kiss on her son’s arms.

Abeer fled her home in 2014 and stayed in the Kurdistan Region’s Shekhan for three years before moving to Erbil’s Baharka camp where she fell into depression. “I was alone. I didn’t have kids. I waited ten years to have Ali,” Abeer told Rudaw English on Thursday.

Seeking some sanctuary away from the trauma of war and violence, Abeer seized the opportunity to join Free to Run organization where she could use her love for sport to gently walk away from the dark cloud of depression.

Free to Run uses sport to empower and educate girls and young women who have been affected by conflict and are now living in camps. The organization provides running training sessions and a life skills curriculum that helps develop critical leadership, conflict resolution, resilience, and communication skills. Alumni of the program often lead the sessions.

“My sister was a member, and she suggested I join them. I told her the organization won’t accept me because I was older than their age limit,” Abeer said.

The organization was founded by United Nations human rights lawyer and women’s rights advocate Stephanie Case in 2014 in Afghanistan, where women and girls have experienced decades of violence and oppression. The link between physical activity and mental wellbeing is well documented. Growing in baby steps, the organization now has five offices in Afghanistan and made its way to the Kurdistan Region in 2018.

“When I started attending the sessions, my mental state improved so much. Even my son Ali – he was alone in the caravan and the sight of people always frightened him, but now he is better. The energy has reflected on him,” Abeer said.

Free to Run works to build leadership skills for women and girls, primarily between the ages of 15 to 25, but sometimes exceptions are made, like for Abeer, country manager Christina Longman told Rudaw English.

“Right now we are working with Baharka and Harsham camps, as we have with several other communities in the past. The Harsham and Baharka camps train separately, so usually, they have once a week a session called life skills through sports and then once a week of running,” Longman explained.

Seven years after ISIS tore through Iraq and Syria, thousands of families remain scattered across camps and informal settlements. The Kurdistan Region hosts more than 900,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees, with more than five thousand families living in Erbil.

Harsham and Baharka camps are home to over a thousand displaced Iraqi families who fled armed groups, especially ISIS in 2014. A total of 942 families live in Baharka camp while 287 families are living in Harsham camp, according to data provided by the Kurdistan Region’s Joint Crisis Coordination Centre (JCC).

Part of the program is to take the skills the women and girls learn through sports and apply them in their daily lives, explained Longman. “It's not just about running the distance. It is about pushing yourself, creating goals, and seeing through these goals.”

Currently 27 women and girls are training for a five-kilometer run at the end of the month.

The program helps them reclaim public space and change their views about their roles in society through sport. As the women and girls strengthen their bodies, they gain more confidence.

“My first hike ever was with the organization. I was carrying Ali and my legs stopped working on a hill. I couldn’t walk. I didn’t know what to do,” Abeer recalled. The program manager began to push her and Ali up the hill, a moment Abeer goes back to when she comes unstuck.

“It renews my motivation and helps me stay determined. It’s a reminder for me to go on,” she said.

Program managers often visit the camps to spread the word about Free to Run, but sometimes they face problems with families because of societal stigmas about women and girls in sport. When this happens, the women and girls help each other.

“Some girls want to join, but their parents don’t let them. When that happens, the program manager and I visit their family to talk to them. Sometimes she goes alone and convinces them,” said participant Ala*, who has been displaced twice.

Ala left the northern Iraqi city of Tal Afar and went to al-Qahtaniyah, Syria in late December 2014, leaving her life behind. “We stayed there around a month then we moved to Shingal. After staying there three months, ISIS attacked us again,” she said. From Shingal, she made the journey to Erbil.

A program officer from the Kurdistan Region and two interns – an American athlete and a medical student from Erbil – are helping run the program. Intern Sima Ayad, who has been working with Free to Run for over a month, told Rudaw English that “it is not only building the participants, but it is building me too.”

Seeing how refugee and IDP families live, “I don’t think it’s something you forget,” she said. “Those girls are pushing every day for something good, and in the back of their heads, each one of them has a goal and a dream that she wants to achieve.”

*Last names have been withheld at the women's request

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment