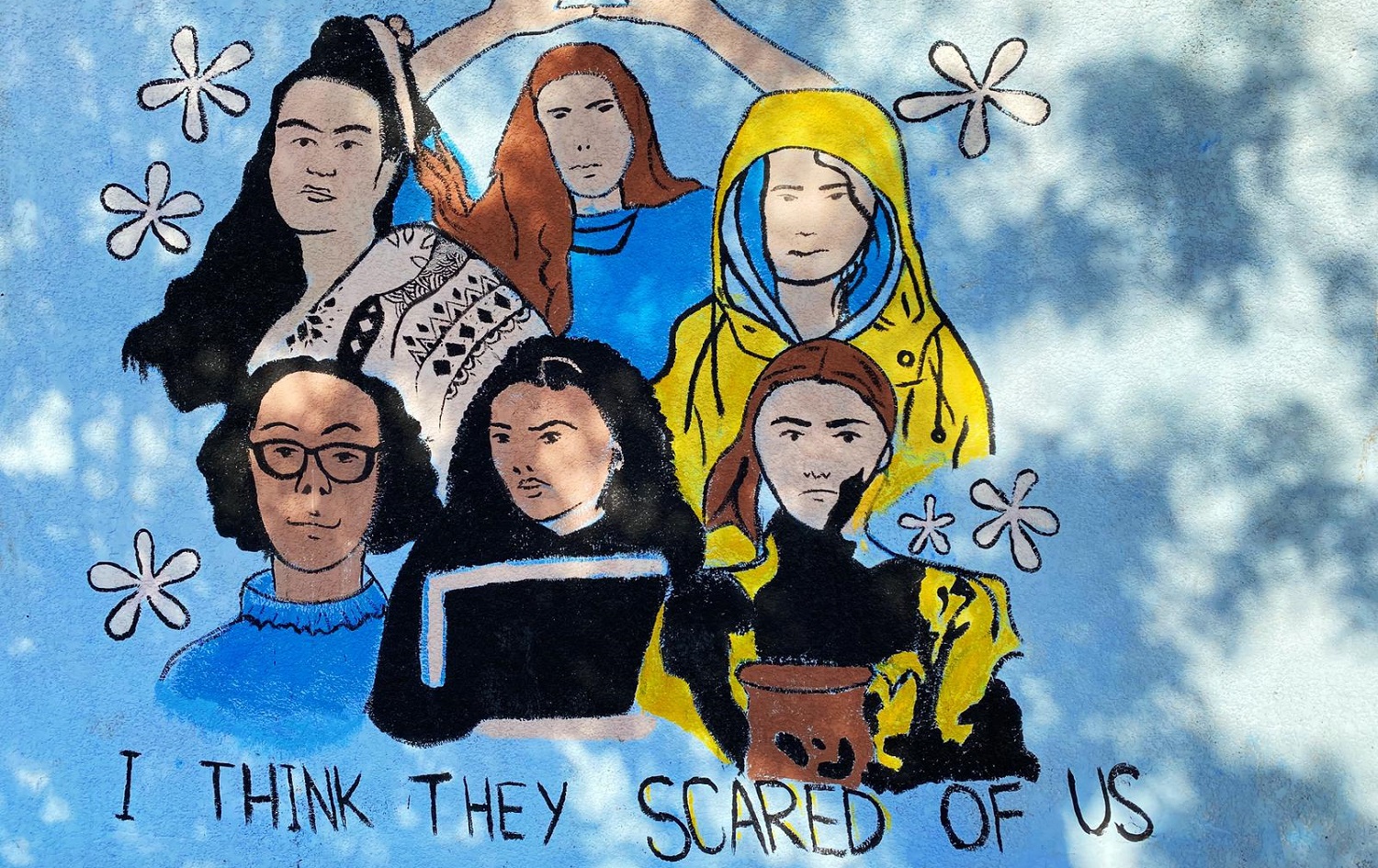

Murals painted along a busy street in Erbil promote women's rights and speak out against gender-based violence, pictured on September 5, 2021. Photo: Anis Ari/Rudaw

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region - Perseng* peered up at the glass ceiling, mesmerized by the stars and the natural lighting they provided to the dimly lit room. Her fascination with the distant luminous balls of gas distracted her from the loud chatter and laughter that filled the small bar she and her friends regularly visited. She remembered thinking how beautiful they were, the stars. Nowadays, she finds it hard to look up at them, because that night he ruined them for her.

“I would have nightmares where I am being raped by other people I don’t recognize. Or it’s faces I do recognize, like people who have hurt me before,” she said. “Or you know, now, whenever I look at the stars, I would relive it.”

For several years, the #MeToo movement has shone a spotlight on abuse and harassment experienced by 1 in 3 women globally, publicizing allegations of sexual violence and supporting victims. The movement started discussions around the world about cultures of violence towards women and girls. The Kurdistan Region, however, has been slow to join the conversation. Sex and violence are taboo subjects, kept firmly behind closed doors.

On July 20, a Twitter thread cracked open the door, published by an anonymous account, it garnered the attention of Kurdish social media. The thread narrated the stories of seven young girls and women who experienced rape or sexual assault, allegedly by the same perpetrator.

One early summer evening, Perseng and her friends decided to go for a drink at their favorite bar. Her friends had work in the morning so most of them left early, but Perseng stayed to finish her drink. She let her eyes wander over the crowd of people, hazy in a cloud of hookah smoke, and recognized a familiar face, her old elementary school friend Kamaran*, and decided to join him. Kamaran was accompanied by two others, a date and a guy named Beza*.

Beza stood tall, showing off handsome features with just the right touch of edginess. He was a musician after all. Throughout the night, they talked about their favorite artists, genres and songs. Beza produced his own music and insisted she listen to it.

“This song is so sad. Be ready,” he warned Perseng before passing her the headphones.

Perseng was hesitant, she expected a low-quality track, but surprisingly enjoyed his music. His lyrics were bleak, describing thoughts of suicide. She empathized with him, having felt similar feelings in the past.

At the same time, she thought he was odd. If the song was interrupted in any way he would repeat the whole track. If an ear bud fell out, he would repeat it. If someone talked to her, he would repeat it. If she was distracted and unable to give his music her full attention, he would repeat it. He made her listen, on his terms.

A single drop of water leisurely made its way down her glass as Beza steadily refilled their drinks, hers without exception always somewhat fuller. Perseng’s slender fingers closed around the glass, the moisture cooling on her heated skin in the overcrowded bar.

The night progressed, tables cleared and seats emptied. Kamaran and his date left together. As the crowd thinned, anxiety started creeping in. Perseng was worried about taking a random taxi home late at night, something that comes with concerns for an unaccompanied woman in Sulaimani. When Beza offered to drive her home, she was more than relieved and happily accepted. He was a friend of friend so she reasoned it would be safer to get into his car than into the vehicle of a stranger. And should anything happen, she had her phone on her. She would be safe.

Trees and city lights blurred as they drove. Perseng faintly heard soft music playing in the background, but she was too distracted by the outside world, colors bleeding into each other, creating a moving, abstract painting for her eyes only. However, she soon realized that he was driving along streets she didn’t recognize.

“Oh yeah, don’t worry. Just want to show you something real quick,” he told her when she threw him a questioning look. He pulled up next to a children’s playground and they got out. She checked her phone to reassure herself, but the device wouldn’t light up and it dawned on her that she must have run out of battery. In mere seconds, all of her security precautions seemed to have evaporated into thin air.

“It’s really late, let’s just drive me home,” she pleaded, reaching for the passenger side door, but Beza was suddenly there. He grabbed her arm and pushed her against the car, his body pressed against her front.

Perseng’s mind was flooded with question after question, most of them blaming herself. How could she be so stupid as to trust a stranger? Why did she go out drinking? Why did she drink so much? How could she be so careless?

Many female victims blame themselves in the beginning, according to Bahar Ali, the director of Emma, a non-profit human rights organization providing psychosocial support and legal counseling to survivors of sexual abuse and vulnerable communities in Erbil. “For us, we just need to convince them not to blame themselves,” she said, attributing many suicide cases to feelings of guilt.

Beza’s lips frantically sucked on Perseng’s neck. Her body froze and her gaze once again wandered to the dazzling celestial sphere above. Observing the stars, she began looking for constellations. “Oh, is that the North Star? They say the North Star is the brightest shining star in the sky,” she said in an attempt to distract him.

When his fingers reached for the buttons of her blouse, she snapped. “What are you doing? Stop!”

“You’re so fucking fine,” was the only reply she received as he continued to assault her, his mouth forcing itself onto hers and his hands fondling her chest.

“Please, what would my mom think? She is worried about me. It’s getting really late,” Perseng pleaded. She hoped that if he thought of her as someone’s daughter, sister or friend, he would stop.

“You’re so fucking fine,” he muttered again. The words robbed her of the last bit of hope she was clinging onto. What was about to happen, would happen, with or without her consent. She closed her eyes as he groped her and began to take off her clothes, as well as his.

Abruptly, fingers lifted from her chest, moist lips detached from her neck, and the body pressing itself against hers, generating an unbearable heat, was gone. He had pulled away from her and she heard the faint sound of laughter carried on a fresh summer breeze.

Perseng, concentrating on what Beza was doing to her, hadn’t notice a group of people coming down the street, towards the playground. He fixed his disheveled clothes, evidently panicked. Saying a quick prayer, she took advantage of Beza’s distracted state, seized hold of the passenger side door and got back into the car. Taxis were nowhere in sight and he was her sole option for getting home. He followed suit. In the driver’s seat, he turned to her, lips slowly parting, but before a single sound could leave his mouth and travel through the tight space of the car, she exploded.

“Please, don’t rape me,” she begged, crying hysterically.

He physically recoiled from her. “I won’t. I didn’t!” he said.

Perseng was confused. However, stronger than her feelings of confusion were her emotions of relief and so she did the only thing that felt right at that moment, she thanked him because, at the very least, he hadn’t raped her.

While driving her home he kept insisting that their interaction was consensual, that she can’t tell anyone he hurt her.

Perseng’s eyes drifted back outside the window. The sky was still accessorized by its usual number of stars, but something was different. As she looked up, she didn’t feel the same joy. The awe she used to experience underneath the night sky was missing. His voice faded to background noise while she blankly stared into space.

Perseng said she will not be taking legal action against Beza because of societal and family pressure. She also doesn’t want to face exhausting court procedures.

This is common, according to Emma’s Ali. “A large number of women who face sexual assault or abuse, do not report it because their family and also the society are blaming the victims, which are the women, not the person who abused them or the men who abuse them,” she explained.

Stigma around sexual violence is high in the Kurdistan Region where the issue is wrapped up in notions of honor. As such, it is often under-reported. Victims often hide the “shame” of the assaults they suffer.

Related: To kill your daughter in the name of honor

Perseng decided to tell her story because she wants justice and she hopes she can help inspire social change.

She is not the only person to accuse Beza of assault.

Viyan* was underage when she said she was first contacted by Beza on social media. They talked for some time online before eventually meeting in person. She said she enjoyed their conversations about music.

One evening, they were in a popular café when he suggested they go someplace else.

“Let’s go to XLine. I want to show you something,” Viyan recalled him saying, a mischievous glint in his eyes that appealed to a teenage girl.

She eagerly and excitedly agreed. She had never been to XLine before but always wanted to go. The old cigarette factory in central Sulaimani had been repurposed as a community center for young artists, providing them with a space to produce and showcase art. The sprawling grounds and maze of buildings was empty and Viyan remembered thinking that if someone wanted to hurt her here, not a soul would notice. However, she dismissed these thoughts because she was with Beza and believed she could trust him.

Although it was still light outside, it was dark inside XLine. He led her to the basement, the place quiet and eerie, vacant bathrooms occupying most of the space. She felt his hand grab hers and drag her into an empty stall. He started kissing her and Viyan liked it.

“Viyan, take your clothes off,” he suddenly demanded.

Viyan was startled and refused, but he persisted. She remembers how he put his hand around her neck and tightened his fingers, making it difficult for her to breathe. She almost blacked out and cannot recall what happened afterwards.

She didn’t see Beza again after that night, but a close friend asked about him and she described their last encounter. “That’s disgusting,” her friend said, visibly appalled. Viyan was confused. Until that moment she had not comprehended what happened to her. She had not realized it was wrong of him to touch her without her consent.

Rudaw English reached out to the accused. He denied the allegations against him, but refused to comment further.

Viyan said she has talked about her experience for some time, but felt unheard. Seeing how people paid attention and supported the survivors whose stories were told in the Twitter thread, she was emboldened to speak out again.

She was not alone. The Twitter thread inspired others to share their stories and social media accounts were created to give a platform to those who experienced sexual assault or rape.

Rojin* was sexually harassed by her cousin at the age of seven. “I was looking at pictures and saw him in one of them and it came back to me,” she said, recalling bits and pieces of the incident.

Her story went viral on Twitter. She said she decided to tell her story in solidarity with other victims. “I wanted to be there for the other victims with everything that's been going on. I wanted them to know that they're not alone and that it was never their fault,” she said.

It’s not just women who are victims. Men are also survivors of sexual assault, facing additional challenges because of social attitudes and stereotypes about masculinity.

Shahid Mohammed was a young boy when he was assaulted. The stories of others on social media brought back his vague memories of the incident.

“I was an eight-year-old when it all happened. We visited them very often since my family and theirs were very close. He was nice and would give me his phone so I can play with it most of the time,” he recalled.

“One day when he called me outside on a snowy cold winter night and said if you want to play on my phone you have to come over there, [and] pointed to an abandoned house,” he said.

In the house, his cousin sat him on his lap to play with the phone. Mohammed said he only noticed what was happening when the man tried to pull down his pants, rubbing something on Mohammed’s anus. “I tried running away but he pushed me harder, I screamed and he covered my mouth with his dirty hands.”

Mohammed resisted for a few minutes until he threw the man’s phone to the ground. The man let him go in fear of his phone breaking.

“Eventually, I stopped thinking about it, and I never tried to remember it. I wanted to forget it and move on with my life,” he said. But it all started coming back to him after he read the “horrible rape stories from a Twitter thread.”

Mohammed chose to go public without anonymity because he wants to see blame finally shift from the victim to the abuser. “I refuse to be ashamed about what happened to me,” he said.

Awareness of gender-based and sexual violence is slowly growing across the Kurdistan Region and Iraq, helped by numerous campaigns by the United Nations, non-governmental organizations, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). More women are reporting the crime. In June alone, the KRG’s Directorate of Combatting Violence Against Women received 1,044 complaints from victims of sexual harassment or abuse.

“A lot of women, especially young girls, are coming to our organization. They are sharing their stories,” said Ali, the Emma director.

The support for survivors who told their stories on Twitter and the waves of people who followed in their footsteps are a sign that Kurdistan’s youth have decided that time’s up.

*Names and some details have been changed to protect the survivors' identities

Additional reporting by Layal Shakir

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment