ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — A multi-storey market teems with shoppers, where customers carve paths through towers of goods stacked high upon each other.

Climb to the floors above, however, and things quickly change. The din of busy shoppers grows quiet, replaced by the occasional squeal from children playing football in the dusty hallways. Fresh laundry hangs on bare concrete walls that overlook Erbil’s ancient citadel on one side, and a graveyard on the other.

“Life in Iraq is nothing,” Hamed*, a shoe shiner, said from the dark two-room flat he has called home for the past seven years.

Around 150 families, almost all of them Christian, have been sheltering rent-free in the upper five floors of the building housing Erbil’s Nishtiman Bazaar since their towns and villages on the Nineveh Plains were taken over by the Islamic State (ISIS) almost seven years ago.

But what was once a refuge no longer feels like one. The building’s residents want to leave, but they don’t make enough money to pay for that journey, and home is too dangerous to return to.

“It’s a prison,” said one man, who preferred to remain anonymous. “Organizations come by every now and then, ask us what we need, and leave.”

“Only journalists visit us – no diplomats, no religious figures, nobody.”

There are small signs of perseverance on the floors above the market. Next to blankets draped over balconies, a cross is fixed to the wall. Like many here, his family hails from Qaraqosh, a large Christian settlement in the Nineveh Plains set to welcome Pope Francis on Sunday.

News of the first-time visit has been received with fervour in Iraq and beyond, but residents in this building hope it will bring help for Christians, who, like them, were displaced by the ISIS onslaught.

People living behind the doors that line the dim corridors speak of former lives in Bartella and Tel Kaif, both Christian-majority towns a stone’s throw away from Mosul, once the heart of ISIS’ brutal reign in Iraq.

While churches have been cleaned, roads painted, and crosses hoisted high for Pope Francis, Christians living in this building say there is little to return to, and no money to fund their journey to someplace else.

“Life was fine before ISIS – there were no problems,” Hamed told us from his home, where a tinsel-framed portrait of Jesus hangs on the wall.

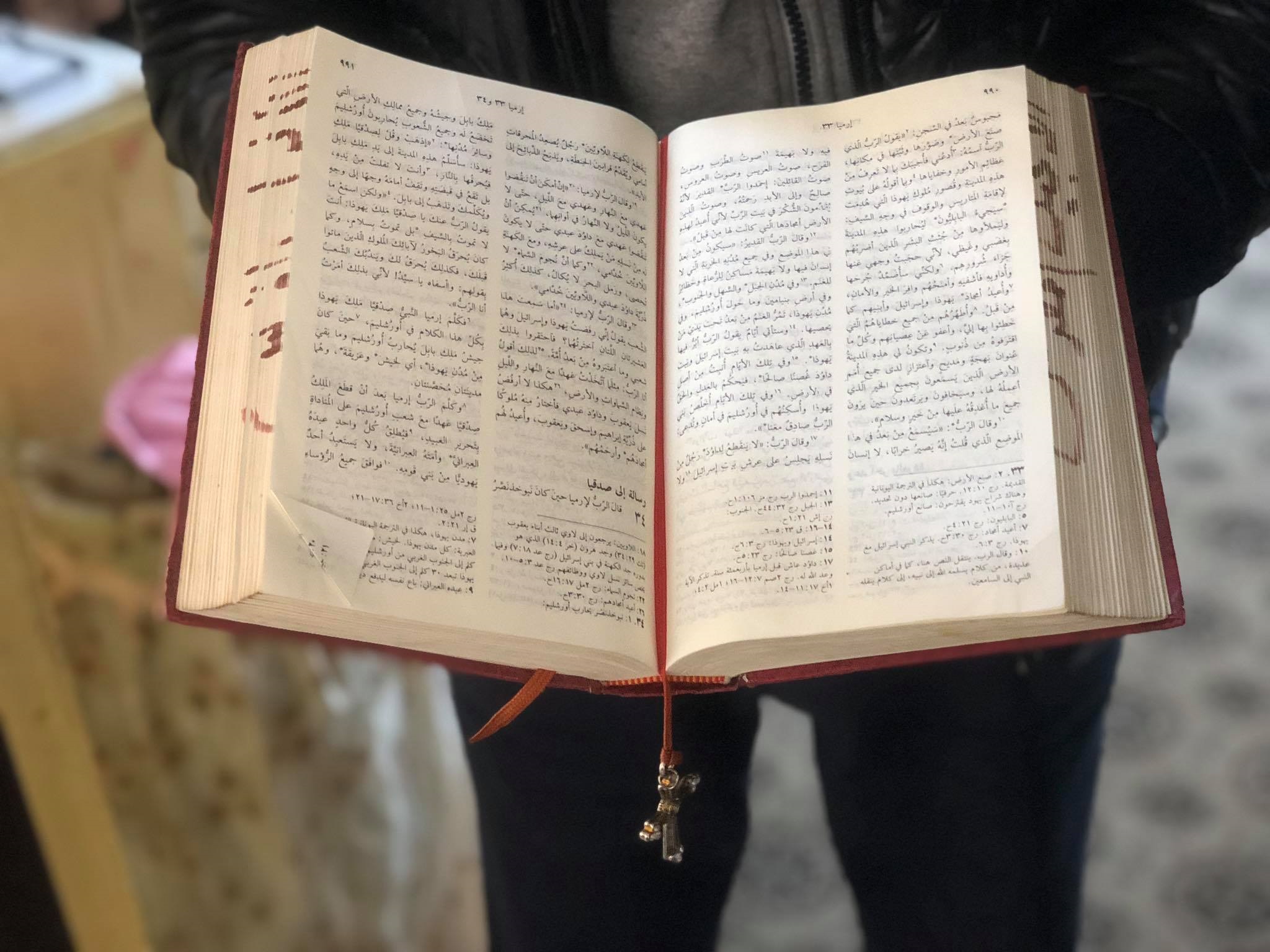

He and his wife fled Tel Keif in 2014, and live in the small apartment with their son and baby daughter, proudly showing us an Arabic-language bible rescued from their town. Now, they say, ISIS still remains a threat - but unemployment and a roof over one’s head are even more pressing.

“For those who return, there is no guarantee of a job or a life.”

More than one million Christians lived in Iraq before the US invasion in 2003, according to Erbil’s Chaldean Archbishop Bashar Warda. After years of exodus and migration, less than 300,000 remain.

While the coronavirus has ground global travel to a halt for the past year, leaving Iraq is high on everyone’s wish-list.

“I wish that we could all leave this country together,” said Hamed’s wife, smiling at a photo on her phone of her sister in Canada. “There are many who want to leave.”

One floor higher, a family from Qaraqosh clear away lunch, their eating quarters separated by a thin plastic curtain. An old woman, hunched over, sits on the sofa and lights up at the mention of the upcoming papal visit.

“It´s a miracle,” Elisa said through her daughter, who translates into Arabic from Aramaic, the language of Jesus still spoken by many of Iraq’s Christians.

Taped to the walls are pictures of the Last Supper and portraits of the Virgin Mary.

The family, who are worshippers at an Ainkawa church, say they have received little help from fellow congregants - and also want to emigrate. But as ticket holders for the upcoming mass held by the Pope on Sunday, the family are hopeful the visit may help them secure a more stable future.

“We hope the visit opens travel for us to leave the country. One of my brothers is in Germany,” the daughter said. “Why would we leave him there alone?”

Warda said that the church is willing to rebuild their homes, and that the villages are now safe for returnees. According to residents, they have been asked to leave the building by June – confirmed by the Archbishop.

“The owner of the building has been generous to offer these places free of charge, however we should respect this man's business and not take advantage of it,” he told Rudaw English on Tuesday.

“Qaraqosh, Bartella – all these places are safe.”

French organisation L’Œuvre D’Orient, which works with Christians across Iraq, said it helped furnish the apartments with the financial assistance of the French government, and some of those they aided have returned back to the plains.

“Each time I come back, I see the Nineveh Plains have made progress,” the organisation’s operations head Vincent Cayol said from Paris. “Houses that haven't been finished have at least been cleared.” Still, he admits, the biggest problem in returning home is a lack of resources.

The result, he said, is a “regular” stream of Christians seeking a better life elsewhere. “It’s a situation we regret, but we accept it.”

For many of the Christians living above Nishtiman, there is only one option in mind: to leave Iraq behind.

*Names have been changed to protect identities

Additional reporting by Dilan Sirwan